Meteorologist and sailor Chris Tibbs shares his top tips of how to forecast and verify tidal streams

Whether racing or cruising, our first thoughts are always: ‘What is the tide doing?’ When I grew up sailing in Scotland, leaving anchorages before dawn to catch a tide was the norm. Not only does tidal flow make a significant difference to our speed over the ground, it also affects comfort; it might be quick with 3 knots of tide under us, but if that’s against 20 knots of wind it’ll be uncomfortable verging on damaging or dangerous.

Most sailing areas around the world are tidal; on our recent passage to Australia the tides and currents could be quite vicious around the islands and atolls of the South Pacific. Information is not very reliable but trying to enter a lagoon against the tide is tricky, if not impossible, as the ebb will often run at six-plus knots.

We made up our own tables from observations to estimate slack water and tide times. This does vary as a high swell adds water to the lagoon increasing the length and speed of the ebb.

Planning

We have been helped for many years by the Admiralty Tidal Stream Atlases – the NP series covers all of UK waters. Knowing the time of high water at Dover we can work out tidal flow direction around the country and, with a little extra work, we’ll also get the rates depending on whether it is neaps or springs. Admiralty charts have tide diamonds on them giving speed and direction.

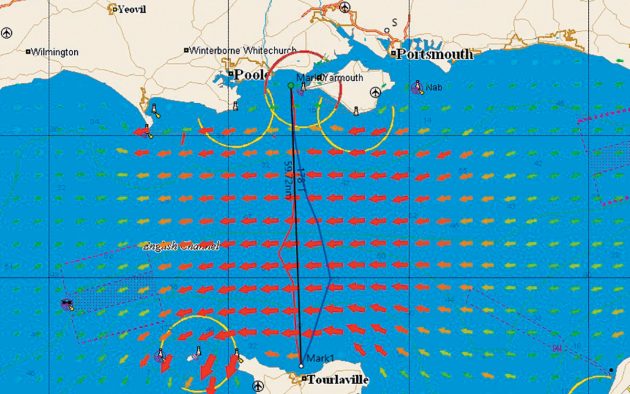

This is great for planning passages in a traditional way with paper charts to determine courses and tidal gates, and I for one would not want to sail distances without them. However, we’re now in a more electronic era and can download electronic forms of tidal atlas and animate them. There is a mass of information at our fingertips but we still have to be able use it.

Article continues below…

Nixon Base Tide Pro review: Rugged watch gives local tides at a glance

I live in a tidal area, where the height and times of the tides are crucial to deciding whether we…

Pro navigator’s tips on how to use the ocean’s currents for an offshore advantage

There are a number of yacht races around the world in which strategic decisions on whether to go into or…

Tidal atlases are a must but away from heavily raced areas, such as the Solent, although the general flows shown in the atlas will be good the detail is likely to be a bit sketchy. Apart from the rule of thumb that the tide will run fastest where the water is deep and less in the shallows, eddies may also be found close to the coast and the tide will turn first near the shore. For this we not only need good charts, but also a good echo sounder.

With GPS we tend to get lazy and do not calibrate our log to the extent that we used to. Having an accurate log and compass to compare with the GPS speed and COG (course over the ground) will quickly tell us what the current is and will indicate where tide lines are.

Tidal atlases work from a reference port for tide times, and these differ depending on the source of the data. Even for Portsmouth (the main reference port for the Solent) there can be over half an hour difference on high water depending on the source. In addition, meteorological conditions will change the time and depth of high water, which makes our starting point variable.

Verify the tide

I use every opportunity to verify what the tide is doing when passing a mark. The tide atlas will not be perfect, but it will give a good guide; there will be a certain amount of interpolation between springs and neaps as well as a change from six hours after, to six hours before, as our tides do not run on a 12-hour cycle.

In low tidal areas and areas without good information we sometimes use a tide stick to measure the current. This can be anything from a complex float with a built-in GPS (which I’ve used at Olympic venues to map tidal flows), to a simple weighted float dropped in the sea by a reference mark (fishing pot or similar). By using a stopwatch and compass, a direction and speed can be approximated.

I have found this particularly useful in the Mediterranean where currents are often wind driven and not very predictable. It became routine at classic yacht regattas in the Med to use a RIB early in the day to check flow rates around the local race area, as these would vary considerably depending on the gradient wind and after periods of rain. Off Imperia in Italy one year there was close to 1.5 knots of current around the headlands, making it important to stay close to the land.

Without a RIB, passing close to any buoy will give a chance to estimate current along with your electronic instruments. Around the cans I use a tidal atlas and keep an eye on the depth of water; tide lines can often be seen by a change in the pattern of the waves or by a line of foam, seaweed, or refuse indicating where there is a change in speed or direction of the flow.

Hitting laylines is difficult across the tide and while electronics help with this, pre-planning and a ready reckoner with boat speed and flow will give an indication of how many degrees to add or subtract to allow for the tide. The more we practice with them the better we’ll get.

Offshore I’m a fan of integrating tides into a routing program, using Expedition software with tides from Predictwind or Tidetech. I’ll run routing with and without tides to get a feel for their effect as well as changing polar boat speeds to determine where tide gates are and if we will hit them or not.

Top tips for predicting tidal streams

- Get the most accurate tidal information that you can, be it electronic or paper.

- Verify it at every opportunity.

- Look for tide lines.

- Your echosounder is important.

- Calibrated instruments will quickly tell you what the tide is and when you cross a tide line. Uncalibrated instruments are misleading.

- Electronics will help with laylines but are only as good as the tidal flow input.

- Pinching to round a mark in adverse tide seldom works.

- If running against the tide, hold the kite to the last possible moment (in light winds after the bow has passed the mark).

First published in the January 2020 edition of Yachting World.