The asymmetric spinnaker or A-sail has helped to simplify downwind sailing, but picking the right one can be the hard bit – there’s just so much choice. Jonty Sherwill investigates the options

What should you be looking for in an A-sail for your boat when the bulk of your season’s racing is a mix of inshore racing round the cans and windward-leeward racing with the occasional offshore event thrown in?

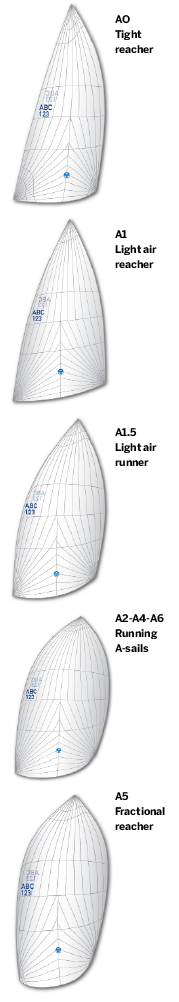

It’s easy to assume than an A-sail – or asymmetric spinnaker – is a fairly standard ‘all-purpose’ piece of kit on a modern yacht, but these sails have come a long way since the early days of cruising chutes and flat reaching sails that were sometimes added to a conventional spinnaker inventory. Today on many racing boats A-sails have usurped the symmetrical kite as the mainstay of a downwind sail inventory.

Neil Mackley of North Sails UK has been at the leading edge of this evolution and explains why knowing the characteristics of the boat is so important: “We look at the boat’s VPP and find out the ideal angles the boat sails at in a given wind speed to determine the size and shape of sail required – it will be a quite different design for a TP52 sailing fast with apparent wind forward using flatter asymmetrics compared with a heavy-displacement Swan 60 running at 170° T.”

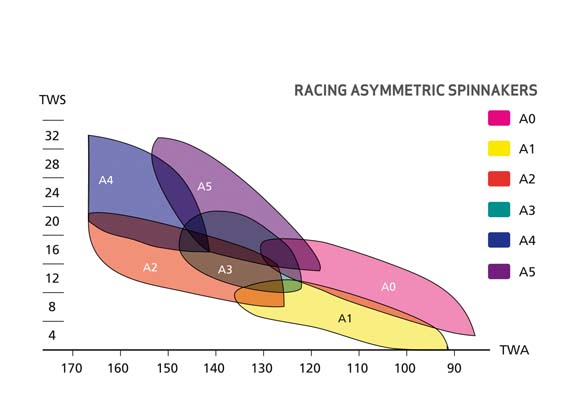

Although setting the right sail is important to make you fast downwind it’s clear that sailing technique and knowing your target boat speeds is also a big part of it. “An example is the J/109 which, in 8-10 knots, will be searching for VMG at 135°-140° true with a flatter-luffed A1 sail. With

a bit more pressure they will head down to 145°-150° true wind angle using a fuller A2 sail that projects the shoulders. When the wind reaches 18-19 knots it will be time to go bow up again and surf,” says Mackley.

Having established the performance profile of the boat, the sailmaker needs to know what type of offshore racing you are planning to do. Will it be an occasional JOG race, a fully crewed RORC campaign, or maybe a double-handed Fastnet Race?

It soon becomes clear that to provide good performance across the full wind range for both reaching and running just setting one A-sail will not cut it in a competitive fleet.

While a typical inventory will usually consist of three A-sails, often including a Code 0 for close reaching, it’s not uncommon to see four or even five asymmetric spinnakers being carried, particularly on the larger yachts.

Under IRC the rating ‘tax’ for these extra sails is reduced as the boat gets larger, typically two points extra per sail over 35ft LOA – but check with the Rating Office.

Code 0 a ‘given’

Peter Kay of One Sails thinks that for a mixed programme of inshore and offshore races the Code 0 is almost a given in a three-sail inventory, alongside an A2 light-medium runner plus a 0.9oz A4 that would run in almost any conditions: “If the racing is to be all inshore you might substitute an A3 reacher or a second A2 for the Code 0 depending on budget.”

A further option is the wide range of Nylon spinnaker fabrics now available. With ten weights of fabric from 0.4 to 3.0 ounces, this allows the sail designer to fine-tune designs for a specific boat’s performance profile and, just like an inventory of headsails, each A-sail will have a ‘sweet spot’ for wind speed and apparent wind angle.

Another factor to be considered is whether the boat is fitted with a bowsprit or uses a conventional spinnaker pole. The latter has the advantage of being able to go ‘pole back’ for running square, but it makes gybing more complicated, requiring the tack of the sail to be swapped to a bow tackle and then back onto the pole after each gybe, which is likely to lose you a couple of boatlengths each time.

For offshore racing with less frequent gybes that may not be such a big issue, but when racing windward-leeward courses or round the cans, where regular tactical gybes will be needed, the activity on deck will also telegraph your tactics to the fleet. “That’s in contrast to a symmetrical spinnaker boat that can float through a gybe at a moment’s notice [at least in light airs],” explains Neil Mackley.

The difference is less marked with bowsprit-equipped boats, but at the top end of the wind range the boat handling advantage swings to the asymmetric boats. Even so, the art of achieving the ‘late main gybe’ (where the kite is fully gybed before the mainsail comes across) needs to be practised to avoid what could be a costly broach.

Long legs

Mackley continues: “A-sails are really good for long legs without gybes and in point-to-point races. On a boat like the Swan 45 with a spinnaker pole our tests have shown that an A2 sail is a faster sail than the equivalent symmetrical S2 with better attached air flow and the narrower head angle which reduces roll.”

Campbell Field, professional navigator and offshore team manager, explains further: “When looking at inventories of A-sails for inshore v offshore racing, one has to consider very carefully the two modes of sailing. Inshore racing is typically VMG-oriented, with a set of trimmers or grinders who can give 100 per cent for a few hours, in moderate to flat seas. Offshore or coastal racing is more varied, much longer legs, so normally sailing a ‘hot’ VMG mode, with longer waves and swell to consider.

“As an example, for an A2 for inshore racing you would be looking for a big shouldered sail, well projected luff, with maximum area sail that requires 100 per cent trimmer and driver concentration to keep the boat in that very narrow max VMG groove.

“[By contrast] an offshore A2 has to be more versatile and forgiving, slightly smaller shoulders (but still max area), slightly straighter luff for a bigger ‘groove’ to allow the driver to sail around waves and absorb the apparent wind swinging from the boat’s acceleration and decelerations.

“This will also preserve some of your trimmers and grinders on the really long runs. A flatter shape would improve the ability to sail higher angles and increase the overlap to a reaching A3 – giving you a better chance of sailing the course you want to rather than the one dictated by the sail.”

With this advance of A-sail design a bowsprit appears to be the logical route on most boats, but how has the progression of the A-sail from a fast reaching sail to an effective deep running spinnaker been achieved?

“While early A-sails were designed the same way as symmetrical spinnakers, with shape in the radial head and a bit of shape in the middle and clews, now our design software means that every single panel has shape in it, so the sails have became smoother and easier to fly,” explains Mackley.

You might think that, with sophisticated sail design software creating predictable flying shapes, this would tend to standardise all sail designs, but it seems there is still plenty of scope for individual design philosophy. Peter Kay of One Sails says: “When running we are looking for maximum projected area so our approach is to shape the sail, particularly the upper leech, in a way that allows the sail to rotate around the forestay, out to windward and which will respond well to tweaker [downhaul] adjustment.”

The effect on your rating

An important consideration when changing things on your boat is the effect it will have on your rating. Some aspects of the A-sail revolution offer potential gains without any rating penalty, eg the Code 0, and the RORC has made sure that the IRC Rule has kept up with these fast-moving developments.

And what of those looking to change from a symmetrical spinnaker with sheets and guys? When upgrading an older boat to A-sails, one of the key decisions is whether to stick with the existing spinnaker pole, with the benefit of being able to ‘pole back’, or invest in fitting a bowsprit for slicker gybing.

While a retractable bowsprit has the advantage of less overall length in the marina it would probably be difficult to retrofit so an externally fixed bowsprit and bobstay is a more popular solution – this is a common sight now on boats of all sizes.

Key points

- Assess what type of sailing will form the bulk of your season – eg offshore, inshore, round the cans or windward-leeward.

- Get a polar performance chart for your boat to identify a baseline for performance.

- Bowsprit or spinnaker pole? The latter will allow you to square off deeper downwind, but is more complicated in hoists and gybes.

- Given a three-sail limit and a mix of inshore and offshore racing, many opt for Code 0, A2 light-medium runner and A4 runner.

- Inshore programmes might substitute an A3 reacher or a second A2 for the Code 0 depending on budget.

- Consider what would be the effect of a change to your rating.

See our 5-tips on racing with an asymmetric