Could hydrogen-powered yachts be built from rocks or plants in the next decade? Toby Hodges investigates yachting’s eco future

It’s becoming abundantly clear that to meet greenhouse gas emissions targets set out in the 2016 Paris Agreement, we’ll need to adopt some radical changes in all lifestyles. Thankfully sailing is, by its very nature, a green activity. In fact, if you wanted to live as carbon neutral a lifestyle as possible, move onto a yacht and go sailing! But for how much longer will we be able to buy glass reinforced plastic boats, powered by diesel engines?

When you consider the energy, materials and waste in composite boatbuilding, it can paint an ugly picture. Ironically, the best way forward might be to revert back to building wooden yachts with hemp ropes and cotton sails, but that is perhaps not the most practical answer to supplying today’s global boating demands.

However, researching this feature has filled me with optimism. There are brilliant minds working in the marine industry and many fascinating solutions for alternative materials and power sources. So how might eco-tech change boatbuilding in the next ten years and what will your next yacht look like?

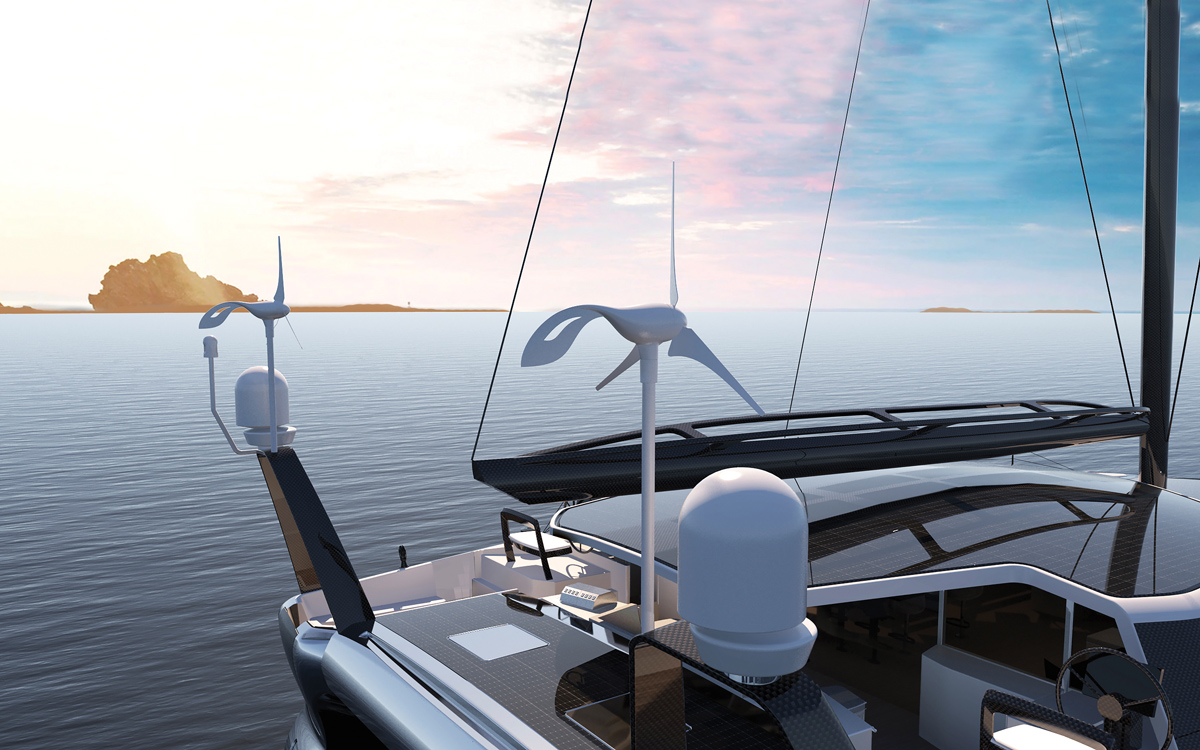

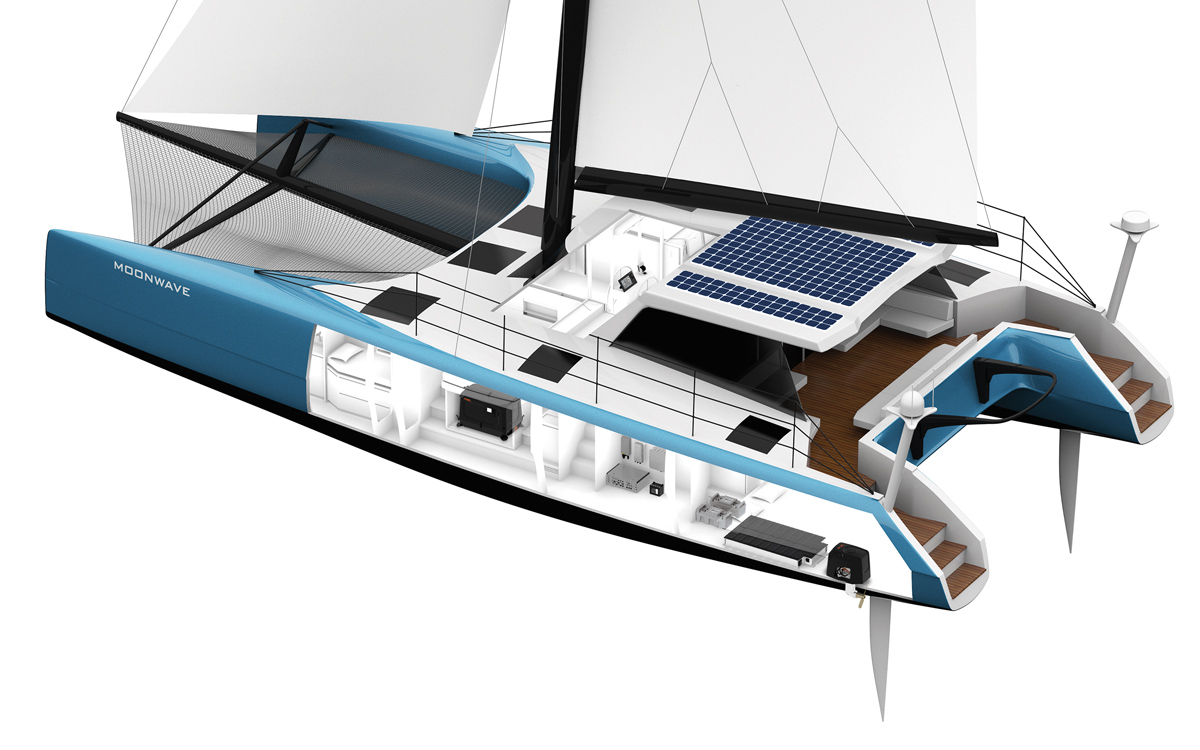

This hydrogen electric cat is midway through build at Daedalus in North Carolina

The simple solution

Technology will continue to make yachts ever simpler to operate. The ability to go daysailing easily will be critical for an increasingly time-poor generation, while powerboaters drawn to the eco credentials of sailing will seek an intuitive format, in yachts that are easy to rig, dock and manage.

Boatbuilders are progressively incorporating greener propulsion and sustainable power sources, and are turning to natural and recyclable materials. Whether they are regulated to do so or not, this is a logical step to take, especially if we, the buyers, demand a more ethical product.

In the next decade we’ll certainly see a marked increase in the use of 3D printing in boatbuilding. Already employed for custom parts, this technology could be used to build hulls and decks – printed structures with natural fibre skins surrounding them could eliminate the need for wasteful moulds.

Article continues below…

4 eco-friendly improvements to upgrade your yacht

1. Ditch the teak Teak is no longer universally popular. The price has gone up dramatically, supply is dwindling, and…

How hybrid sailing yachts finally became a feasible option

Every sailor is familiar with the wet cough of the diesel engine, and the acrid smell of its exhaust. For…

There are already bodies in place concentrating on the reduction of waste and energy use in boatbuilding, while promoting recycled and low-impact materials. 11th Hour Racing is doing commendable work here. The common boatbuilding technique of using hand laid-up polyester certainly looks increasingly endangered.

Search for speed

The most effective way to minimise your carbon footprint afloat is to sail, so there is a strong argument for choosing performance yachts, which can harness the wind more efficiently. Large yachts and catamarans have an advantage too as they provide the deck space to host numerous solar panels and the speed to incorporate regenerative propulsion.

During its research for the Outremer 4E project, and new 55, Grand Large Yachting found that the usage of a yacht accounts for a much higher carbon footprint than its build. If you are able to sail in five knots of wind, then you can sail 95% of time in the Mediterranean, it says (data from western Med June-September).

Outremer’s 4E prototype will be used by cruising guru Jimmy Cornell for his next circumnavigation

To achieve this performance requires minimising weight, but what are the best alternatives to using the traditional high strength-to-weight ratio synthetic fibres such as glass and carbon?

Basalt fibre has long shown promise and is being used by new French catamaran brand Windelo to build its hulls, with PET (recycled plastic bottles) cores. Basalt is transformed from volcanic rock (with minimal CO2 emissions), so the fibres are particularly resistant to heat and are recyclable.

However, it is the fibres from plants that could offer the most potential for boatbuilding. Flax in particular, the plant from which linen is derived, looks like becoming one of the most effective alternatives for use in high-strength composite applications.

Natural promise: Linen fibres are derived from quick-growing flax plants

Boats from plants?

The flax-based products of Swiss company Bcomp have already been used effectively in motorsport bodywork and snow skis for their combination of stiffness and vibration damping.

Paul Riley, a composites expert now marketing Bcomp products for marine use, says that flax is lighter than glass fibres, with similar stiffness and significantly lower cost than carbon fibres, yet with up to 75% CO2 savings. “I think we’ll see this coming into mainstream yachting in the next two to three years,” he says. “Manufacturers need to take a stand and switch to less environmentally impactful materials, which will also provide improved health and safety for their workers.”

Flax grows from seed to crop in eight weeks, rarely needs irrigation, and chemicals are not required. Thus far it has been used by German yard Greenboats, including on the 2016-built GreenBente 24, and superyacht builders Baltic Yachts. News that Gurit, global leader in composite material supply, will be the worldwide distributor for Bcomp, could lead to a broad adoption by marine manufacturers.

A Tesla Model S electric race car clothed in Bcomp flax composite bodywork

Visitors to the Düsseldorf Boat Show this year may have seen the potential of this fibre on the Greenboats stand. Its Judel/Vrolijk-designed Flax 27 daysailer became a test-bed for numerous natural and recycled materials. The hull is made from flax and bio resin with a PET core, the deck from cork.

Greenboats’ founder Friedrich Deimann told me how frustrated he became with using composite materials, especially coming from a wooden boatbuilding background. “It takes five times as much energy to produce glassfibre than linen fibre,” Deimann reports, showing me the plants from which he built his beautiful clear-coated daysailer.

Greenboats has been using Flax or Natural Fibre Composites (NFC) since 2010. And it minimises the use of moulds by using a stitch-and-glue technique to build panels. Deimann’s company shows what is possible, but he admits a lack of trained personnel and the costs of small-scale production are the current issues.

The Greenboats Flax 27 daysailer has a hull made of linen fibre and bio resin with a core of recycled plastic bottles

Another is resin control. “You can’t use hand lay-up with flax because it’s a natural material, and without compression the fibres can absorb a lot of resin,” says Deimann. “By vacuum-infusing the resin, you compress and control it.” Vacuum-infusing resin brings its own environmental issues because the plastic used in the bagging process creates a significant amount of landfill. Some boatbuilders have already found a clever solution here in reusable silicone bags.

But the resin itself still remains an issue for chemists to solve. Pure bio resins exist already, but for the high-performance epoxies required in boatbuilding the natural content might only be around 30%. Entropy resins, bio-epoxies used in marine, snow and surfboards for example, are manufactured by replacing petroleum-based carbon with renewable plant-based carbon – by-products from the agricultural industry.

Recyclable boats

Elsewhere, yards have been forging ahead with various technologies that offer a cleaner end of life potential. The hull of the mini 6.50 raceboat Arkema 3 was made from a recyclable thermoplastic composite using Elium acrylic resin, for example, which can be ground down and reused to manufacture new parts. And many RS dinghy hulls are made from rotomoulded and recyclable polyethylene.

A more persuasive argument for cruising yachts in particular is to use aluminium or wood composite hulls, materials that can be recycled and don’t require moulds. Vaan is a new Dutch brand of aluminium catamarans, which are not only long lasting and recyclable, but made of mostly recycled parts. Hulls and decks are giving a second life to old window frames, traffic signs and number plates.

A more persuasive argument for cruising yachts in particular is to use aluminium or wood composite hulls, materials that can be recycled and don’t require moulds. Vaan is a new Dutch brand of aluminium catamarans, which are not only long lasting and recyclable, but made of mostly recycled parts. Hulls and decks are giving a second life to old window frames, traffic signs and number plates.

Meanwhile, the benefits of using high-tech timber construction are clear for all to see thanks to Spirit Yachts. Its strip-planked technique makes for a very stiff, lightweight structure, with hulls made from largely renewable materials. Indeed, the beautiful new Spirit 111 flagship is being labelled as one of the most environmentally friendly superyachts ever.

Managing director Nigel Stuart has instigated a network of green initiatives at the Ipswich yard and in its yachts. The Spirit 111 includes energy-saving appliances throughout, including ultra-efficient hydraulics and genset, and a regenerative propulsion system for its Torqeedo electric drive.

And it is this latter element – power – that will surely be the primary focus for making cruising yachts greener in the coming decade.

Going electric

Torqeedo and Oceanvolt have led this drive so far, with Volvo Penta now ramping up its electromobility technology. And although Torqeedo has already delivered 100,000 electric drives, this represents only a small fraction of the market, according to CEO Dr Christoph Ballin.

“So far, only about 1.3% of marine propulsion systems are electric… we need to put the foot down and do more,” he states. Over the next decade, Ballin sees serial hybrid power as the optimum solution for yachts, systems that involve a large battery bank with a mix of solar and hydro power generation. This reduces the CO2 footprint by around 90%, but with the safety net of a ‘diesel range extender’ – a compact generator, says Ballin.

Moonwave is a Gunboat 60 recently refitted with the latest generation of Torqeedo’s Deep Blue electric drive system

Such a system caters for normal sailing and living requirements using only battery power. “The role of the generator is reduced from providing everyday energy for living on board (heating, cooking, washing, aircon) to emergency use, if you will. And the role of the combustion engine for driving the boat is completely eliminated.”

But what about hydrogeneration? Combined with enough solar panels, surely this will enable us to dispense with fossil fuels on board altogether? “I fully agree, hydrogeneration in terms of using the propeller to create power under sail is one thing that is here to stay,” Ballin believes.

ZF steerable saildrives are being integrated with Torqeedo systems for hydrogeneration

But it is dependent on the speed and size of the vessel. He points out that if you have a fast boat you can generate all the electricity you need while sailing: “We have a customer with Gunboat 60 which generates 10-15kW”.

Battery storage

“The limitation here,” points out Ballin, “is how much energy you can store in a battery, because of the energy density that batteries offer.” Torqeedo’s Deep Blue technology and use of BMW’s i3 high voltage lithium-ion batteries gives it an edge on competitors.

But is the reliance on lithium boat batteries as a ‘clean’ source of energy storage simply solving one problem by adding another? The questionable mining ethics surrounding the cobalt used in many lithium batteries has been widely reported and the question of battery recycling still remains unanswered.

Ballin foresees supply chains becoming more ethical from a human rights standpoint. He explains that BMW is now controlling the entire supply chain for its batteries, including sourcing the raw materials, to avoid inhumane working conditions.

This makes for another whole topic, as does the recycling issue, to which Ballin alludes to the potential for a second life for marine batteries in powerwalls and energy storage before they go into any recycling for cobalt extraction.

“We are in front of the largest mobility revolution since the introduction of combustion engines,” Ballin states. “We have to live with the fact that the stages in this transformation programme are all imperfect – and will be for more than ten years.”

Looking ahead, Ballin sees three key scenarios for what is possible for climate neutrality on boats: battery electric vehicles; hydrogen-power; and synthetic fuels. “The rule for sailors I think will be that wherever battery electric vehicles are feasible those are the preferred ways to go forward.

“If battery electric vehicles do not give you enough power, which is almost always the case for oceangoing vessels, then you can go to hydrogen for example… It will become mainstream to have a climate-neutral range extender.”

Hydrogen power

So could hydrogen be the holy grail of energy for yachts? Hydrogen fuel cells work by converting hydrogen (from seawater) to positive and negative electron charges. So far this process has been used as an energy source only by a few pioneering vessels, including Energy Observer, the first energy autonomous hydrogen boat to circumnavigate. And Race for Water, a solar and kite-powered multihull carrying a conservative amount of hydrogen (200kg) in 25 bottles, is currently three quarters of the way round the world.

Solo racing sailor Phil Sharp has been demonstrating a hydrogen fuel cell in place of a diesel engine to generate power aboard his Class 40 OceansLab. He believes larger scale commercial shipping and marine craft can adopt the technology to reduce their carbon emissions to zero.

For leisure yachts, however, hydrogen fuel cells are not yet economically feasible. Torqeedo’s Ballin explains the practical limitations: “The energy density of hydrogen per kg is a lot better than petrol or diesel, but the volumetric energy density is about 1/13th of diesel.” This means much larger fuel tanks are necessary – although these volumes can be reduced under pressure.

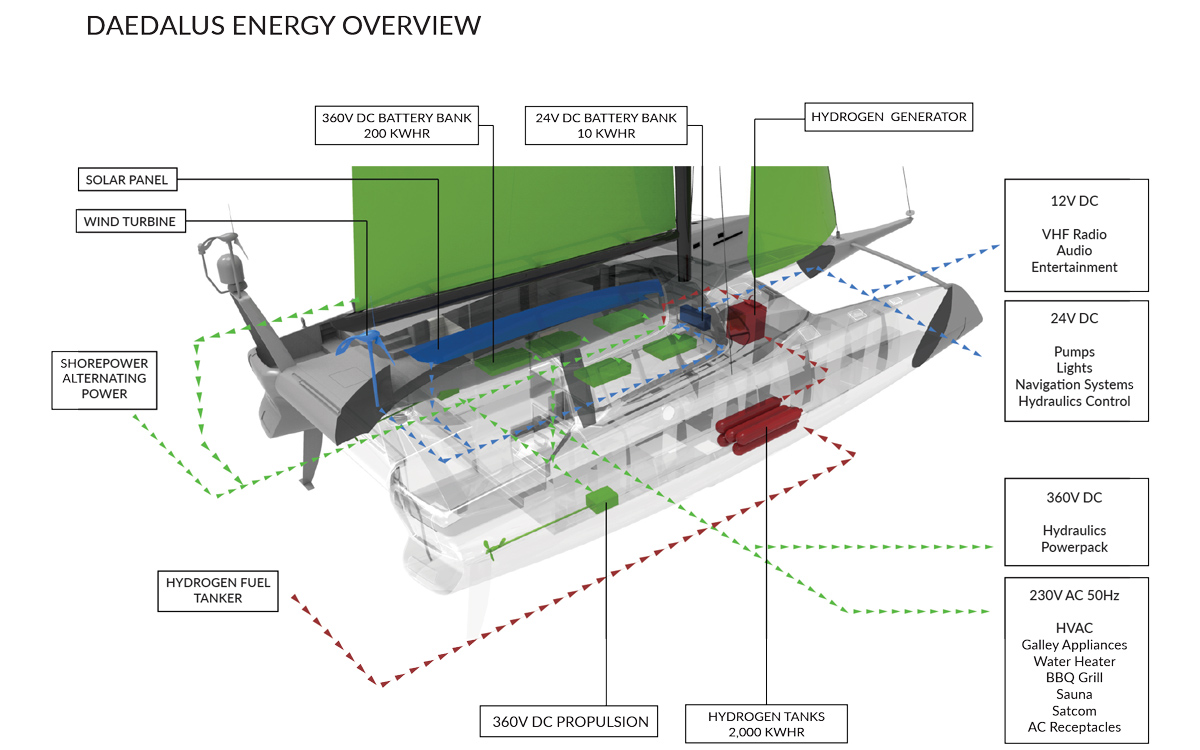

That helps to explain why hydrogen has been adopted by only a handful of (large) yachts thus far. A pioneer of the technology is Daedalus Yachts, which is midway through building the first hydrogen-powered superyacht. “Over the past two years we have conceived and developed not only a complete hydrogen electric marine propulsion system but also a clean energy micro grid with the only emissions being oxygen and pure water,” says Daedalus’s founder Michael Reardon.

The overview of the Daedalus renewable energy and power system

The 88ft catamaran is being built to full commercial survey for world cruising for visionary Stephan Muff, who created the technology for Google Maps. The Daedalus electrolyser (which converts water to hydrogen) is the same as has been used in US spaceships and NATO submarines, so the North Carolina company is quietly confident it’s onto a reliable power source.

For the shorter term however, sailors should look to solar and battery technology, where we can assume continued improvements in efficiency and capacity for reduced costs. Building photovoltaic cells into biminis, decks, masts, and sails is already feasible.

Sail power

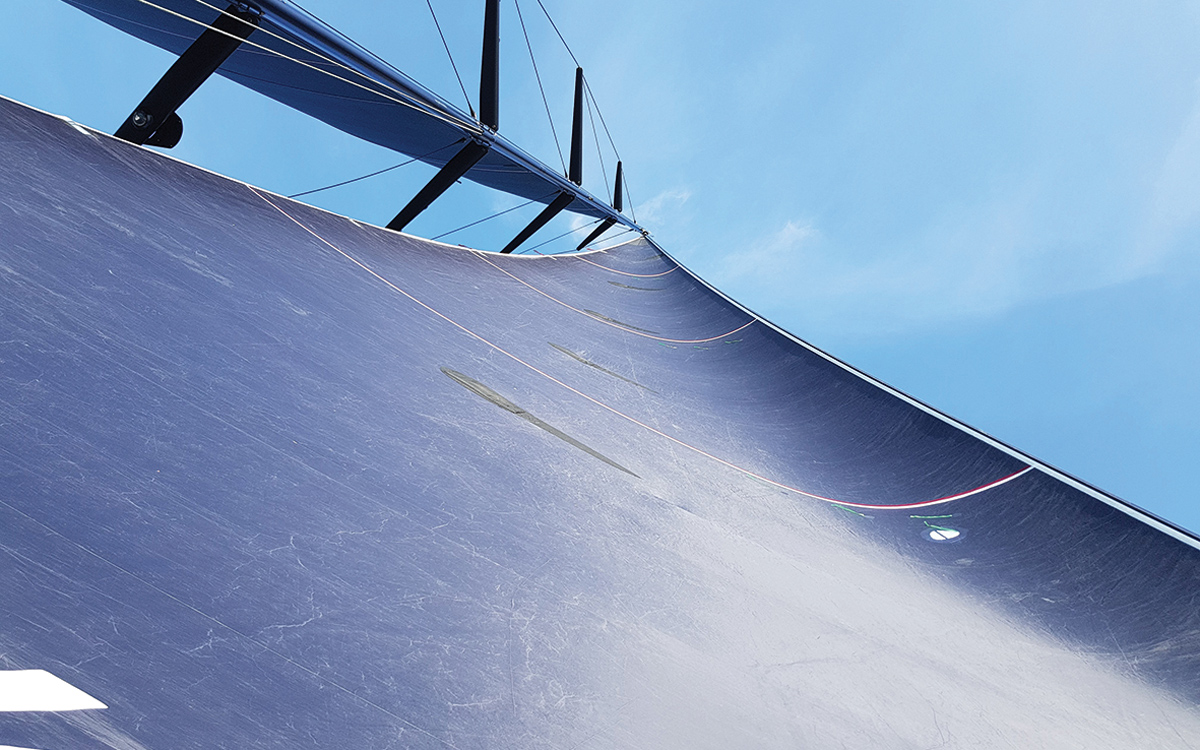

Using sail power alone whenever possible is an obvious objective. But it’s the sailcloth itself that is arguably the most disposable component, particularly aboard racing yachts. Laminate sails with a Mylar membrane can’t be recycled, so many used sails go to landfill, or are abandoned in sheds and shipping containers.

OneSails 4T Forte membranes are recyclable sails that use STR stripes, a high modulus fibre produced by compaction of polymer to create a flat ribbon

Polyester/Dacron sails are largely thermoplastic so can be melted and reformed (although typically coatings such as melamine render this highly problematic). However, other than turning them into bags and accessories, what are the options for sails with synthetic fibres, high modulus yarns, which are notoriously difficult to chop up and repurpose?

OneSails has been ahead of the game here with its 4T technology. It uses a recyclable base polymer and replaces the glues and resins with heat fusion. The result is a composite single structure sail, which uses a low-stretch technology to avoid Mylar or taffeta, for a completely recyclable sail. “This technology is the only genuine sailmaking system that offers the opportunity for sailors to recycle ‘end of life’ sails,” says OneSails UK’s John Parker.

North Sails’ 3Di products also avoid Mylar film and the company is working to recover raw material from used sails to turn it back into polyester fibres. North’s commercial director Tom Davis, who has overseen its cloth business for the last 20 years, sees two key areas of development with greener sails. Firstly with the raw materials: “I will be very surprised in the next few years if materials going into sails aren’t substantially bio-based.”

With its partner, Steelhead Composites, Daedalus has built the world’s only certified hydrogen containment vessel

And secondly, with what he terms the ‘back end’: “A very high percentage of the total acreage of sailcloth in all areas will be repurposed/recycled.” Again, he sees the quickest changes happening with polyester and reports that North is already using recycled PET films, which are chemically indistinguishable from oil-based film.

Davis has been impressed by the speed of the technology in these areas. “In the sailcloth/making business, we’re not big enough to be producing new yarn or filaments – that’s really a petrochemical level business. But we are the beneficiaries of the technologies those companies develop.”

So in the case of high modulus yarn products, North is working with a company that is producing a bio source for the monomers that become polymers and then become high performance yarn and fibre. “So instead of pumping oil out of the ground and converting it to plastic, they’re starting with trees and ending up with very high performance plastics,” Davis explains.

Positive thinking

It goes without saying that future yachts should be well insulated, durable and with very low energy loss and consumption. Battery banks and renewable regeneration will mean there’s little requirement for fossil fuels. Water filtration in and out of the boat is increasingly important. For those who spend long periods aboard, the growing energy efficiency of watermakers means there is simply no call to ship bottled water. Self-sufficiency rules.

The dissolving print your anchor leaves in the sand should be the only evidence a yacht ever leaves behind! I’m confident the next decade will bring a tidal wave of innovation in the marine sector. And with the right collective mindset, the future is indeed bright – it’s exciting and it’s green.

First published in the April 2020 edition of Yachting World.