How do you prepare for the Volvo Ocean Race? Helen Fretter gets exclusive access to one of the favourites, with Dongfeng Race Team

A plume of spray smokes from the windward rudder of Turn the Tide on Plastic. The guest crew on board are whooping, giddy with the exhilaration of the Volvo 65 blistering along in a late summer breeze blowing warm off the Spanish coast. Skipper Dee Caffari glances over her shoulder, her smile visible to us from 65ft away, as she leads the fleet in the first pro-am race of the Volvo Ocean Race.

Charles Caudrelier is not smiling. At the wheel of Dongfeng, all he is focusing on are the few feet of churning white water between our bowsprit and the stern of Turn the Tide, trying for an overlap. It doesn’t matter in the slightest if we get one – the pro-am race doesn’t count towards anything, it’s half an hour of reaching around the bay to give invited guests a tiny taste of what the VO65 can do. But it’s still a race, of sorts.

In a few days time Caudrelier will set off to try and win the Volvo Ocean Race with the Chinese-backed team (he’s already won it once, with Cammas on Groupama); trying to switch off the competitive instinct at this point is like trying to turn off hunger. It’s his second race as skipper, he’s spent more four years of his life preparing the team for this point, and they have left nothing to chance.

Caudrelier spots an opportunity to round inside Turn the Tide, overtakes, and moves into the lead. The guests get a turn to drive, Dongfeng takes the winners’ gun, and the on board reporter sets up some souvenir photos. There is still no whooping or cheering from Caudrelier, Stu Bannatyne, the down to earth Kiwi watch captain, or the polite Chinese crew crewing the boat for the pro-am.

Showmanship

The pre-start razzmatazz of the VolvoOcean Race turns all the crews into dog and pony show players – a show that repeats 11 times in this edition. Some enjoy it, others may be grinning through gritted teeth. Caffari looks to relish the chance to talk about her crew’s ecological message. David Witt, skipper of Team Sun Hung Kai Scallywag, jokes about using the race to lose weight.

Caudrelier doesn’t seem to be enjoying it much. He and his team are itching to get the real racing started. To get out of Alicante, where the pop-up team bases are rammed full of sailors, guests, and support staff attempting to work through a jam-packed schedule of media visits, final briefings and jobs lists in a sweltering unseasonal heat.

As one of the biggest teams, Dongfeng’s village base is even more of a hive than most, despite a separate glossy Dongfeng corporate base next door. There is no respite from the constant noise and no privacy – even the physio’s massage couch is jammed between the beer fridge and the PR staff’s desks. Along the dock shipping containers are lined with everything the team might conceivably need over nine months, labelled and collated in complex spreadsheets (although, in a rare moment of disorganisation, there is no bottle opener for the beer. It’s clearly not a priority).

Dongfeng had an eight month build up to this race with some good indicators, such as winning the Fastnet Race last August, and some less positive. They arrived into Alicante on the back of a poor Prologue Race result, finishing 6th in a light winds lottery.

I ask Caudrelier how the team regroups after such a disappointment? “We have a good team spirit and we don’t worry about that. The most important thing is to have pleasure in sailing together and that’s what we’re going to work on.”

His manner says otherwise. Caudrelier will enjoy this Volvo Ocean Race if Dongfeng does well in it; that much is patently obvious.

“Charles is absolutely focused on one thing, and that’s winning,” observes watch leader Daryl Wislang, who joined Dongfeng after winning with Abu Dhabi last time. “He drives everyone else on the team to do the same. You can really see the emotion in his eyes and body language when something doesn’t go quite as planned.”

Stu Bannatyne, Daryl Wislang and Carolijn Brouwer are among the hugely talented and experienced signings onboard Dongfeng for this year’s race

This is the second Volvo Ocean Race for Caudrelier as Dongfeng skipper. Last time theirs was a tale of surpassing expectations. They had a complex build up, tasked with bringing on a squad of Chinese sailors with little real experience, let along ocean racing knowledge, into competitive Volvo crew.

Precious months were spent on crew trials, on shipping the 65 to and from China, and on melding a team of hardened French racers with ‘rookie’ Chinese sailors who spoke little English, no French, and were unfamiliar with everything European from the weather to food. Their Lorient team base had a ‘swear box’ to pay into if anyone spent too much time talking in French, Cantonese or Mandarin. And yet, they finished 3rd.

This time around things are very different. Team director Bruno Dubois gave the backers, Chinese car and truck manufacturers Dongfeng, three options going into this race. “Either they go for a full Chinese team, or a more international team with more chance to win, or both. I said: ‘What about we do two boats?’”

They chose to go with the option that gave them the biggest chance of taking the trophy. While sailing fans celebrated Dongfeng’s rise from underdog to podium finisher in the last race, when it comes to Chinese audiences, winning is the only story that counts. This time they want to be – maybe need to be – 1st.

At a slick press reception in Paris in May, Dubois unveiled the squad and outlined their ambition. “The 1989 win by Steinlager: this is the style I want to win this bloody race in!” The aim was not just to win, but to take 1st in every leg.

In Alicante, with the start looming, he was more circumspect. “That would be fantastic, but don’t forget Steinlager won because the boat was faster.

“But I know Peter Blake inspired Charles a lot, because he doesn’t want to just [get] a good sailing result, he also wants to inspire people. And to be nice, to have a sort of spirit – you can feel when you stay with our team that there is a spirit and it’s not coming from only me, it’s coming from Charles, and all the guys.”

How would Dubois define that team spirit? “One word: it’s called family.”

The build up to this year’s Volvo Ocean Race was a tense and unusual week, the race village swirling with rumours following first the announcement that event CEO Mark Turner would be stepping down, and then the dramatic sacking and reinstatement of Team AkzoNobel skipper Simeon Tienpont (see page 14). Even the solid Dongfeng squad was not immune from upset, but while other teams disintegrated, Dongfeng closed ranks.

“We had a couple of issues thisweek, an external issue that touched the team, one person particularly. And when we resolved it, some of the girls were crying because they were so happy, they can see it’s such an important part of what we try to do,” recalls Dubois.

Close knit

“Anyone that [is] not fitting into our family does not belong there. They just go, they just fade away… it’s difficult because it’s a little bit like the Mafia!” Dubois says.

The Dongfeng family is tight, but it is also diverse. Last time around a coterie of French sailors had to teach the novice Chinese sailors how to work their way. This time around the team has a much wider range of experience, every player bringing their own way of doing things.

The team combines French, Kiwi, Chinese, Dutch and English backgrounds

“There are a lot of different backgrounds, different cultures, different nationalities, it does give difficulties for sure because everyone has a different way of doing things, but also unique opportunities. Instead of everyone wanting to do it one way there’s three options and we’ve tried them all, and no one takes it personally if we go with one,” explains bowman Jack Bouttell.

“I think that’s really Charles’ biggest job in managing this, but everyone’s here with the same mindset, the same goals, and the same expectations of the crew.”

While the Dongfeng team is confident in their squad, this edition of the Volvo Ocean Race has depth of talent across the entire fleet. Having good sailors will not be enough.

The biggest advantage the returning teams of Dongfeng, Brunel and Mapfre carried into the early stages of the race is knowledge. With identical boats and sails, the only variations are in set-up, putting a premium on data: sail crossover charts, optimum rudder angle, sheet loads. Mapfre and Dongfeng spent some time two-boat testing, an exercise Caudrelier says was ‘an amazing benefit’.

Sanxenxo 2 Boat testing with Mapfre

The team also put in months training out of the former Groupama team base in the brutalist Lorient submarine dock, an unrivalled facility with a vast sail loft and technical area, plus on-site gym, tech rooms and kitchen.

In Alicante, before the race start the teams were nervously assessing each other’s sail choices, with team RIBs openly tailing their rivals to photograph and analyse set up. “It’s something that everyone does,” says Wislang. “We do the same. We’re lucky that our coach does it for us so we don’t have to, and then we analyse it afterwards.

“You can trim the boats completely differently and have the same result in speed. You can get 96-97 per cent of the boat speed pretty quickly; it’s the other three per cent you’re looking for.”

Continues below…

Ambition, nerves, and espionage: final countdown at the Volvo Ocean Race

The first race that ‘counts’ for the Volvo Ocean Race, the Alicante in-port race, takes place tomorrow. The seven teams…

How to follow the 2017-18 Volvo Ocean Race – expert analysis, behind the scenes and direct from the boats

The start of the Volvo Ocean Race is upon us! The first leg kicks off on 22 October. See how…

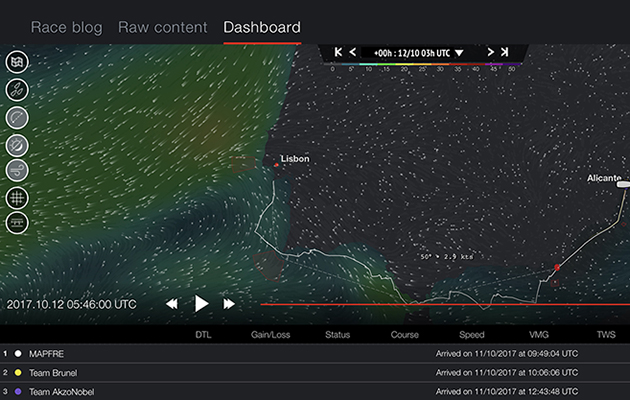

MAPFRE wins Leg 2 of the Volvo Ocean Race, Dongfeng fight back to hold second

The ‘Cape Doctor’, the dry south-easterly breeze which blows onto Cape Town, was in full force for last night’s arrivals…

Much of Dongfeng’s campaign has been about eliminating risks, and seeking out marginal gains – that magical three per cent. Boat captain Graham ‘Gringo’ Tourell is another team member Dubois calls family. When I ask Tourell what the recurring repairs have been on the red 65, he literally scratches his head. Nothing springs to mind, he reports – a big contrast to last time around when the team had repeated rig problems.

There’s little chance of concealing problems or damage: The Boatyard, the event-run pit lane-style service centre, is not only shared by all teams but wide open to the public. If anyone comes in needing repairs, the whole race will know about it.

Pork fat and algae

The humans have also had a high tech preparation, although it might not look like it one morning on Alicante beach. Neil Maclean-Martin is human performance director, and responsible for the sailors’ nutrition, fitness, and rehab. He has the physique of someone who runs ultra-marathons (he does) and a manner which suggests the sailors will do what he says (they do).

The morning I join them he has the crew kicking around bean bag hacky-sacks (never take Jérémie Beyou on in a keepy-up contest) to warm up before lunging and doing yoga stretches on the sand. It’s a brief moment of calm in the pre-start frenzy. Caudrelier’s daughter is quietly playing barefoot in the sand.

Then a one-armed wrestling contest and a frisbee match – fiercely competitive of course, with Marie Riou diving to the ground to win a point – followed by a plunge into the warm Med. Horace chases Jack, Caudrelier wades in hand-in-hand with his youngest child. It’s a carefully orchestrated opportunity to decompress.

“The sailors know it’s a time they can speak more freely, and a time they can be more spontaneous,” comments Maclean-Martin. “It can seem a very nice calm atmosphere, but it’s actually got some really nice functions as well.

When the sailors get in after an offshore race leg, he is waiting to assess injuries, measure weight, skin fold thickness and limb girth, monitoring how much hard won muscle has been lost.

“We’re trying to challenge the dogma that these guys come back pre-diabetic, totally destroyed, their leg muscles have totally wasted away. We understand now much more how to control these things.”

Later I meet him in the team container as he packs food for the leg ahead. Each sailor’s rations are individually calculated. He lays out a full day’s menu – freeze dried meals, protein smoothies, nut bars (700 calories a pop and the closest the sailors get to a treat, no blood sugar-spiking chocolate bars), supplements and snacks like beef jerky.

Spirulina algae, pemmican pork grease, as used by Arctic explorers such as Shackleton… nothing is off the menu if Maclean-Martin thinks it will bring some benefit. In a race once founded on beer and cigarette brands, the Dongfeng crew drink green tea rather than instant coffee, to avoid sabotaging carefully optimised sleep cycles.

Leg 4, Melbourne to Hong Kong, day 08 on board Dongfeng. Drifting in the doldrums with no wind. Photo by Martin Keruzore/Volvo Ocean Race. 09 January, 2018.

He takes a moment to check that something appetising shows through the food bags – all the nutritional balancing is for nought if the sailors don’t eat it – before sealing them. Bowman Jack Bouttell’s daily bag contains between 5,000-7,500 calories and is almost uncloseable when fully loaded. In the container, boxes are stacked 5ft high with hundreds and hundreds of packets and sachets to be packed, checked and loaded for each leg.

Such is the life of a top-level professional race team – paleo food supplements and biometrically optimised workouts, every piece of information, from muscle mass to runner load, recorded and analysed.

Someone suggests I talk to the team’s sports psychologist – another key part of the modern athlete’s armoury. I ask Daryl Wislang what they work on. He cracks a sheepish grin; he’s never actually met him. Not his thing. This is still a team of sailors after all, people who live to challenge themselves against the uncontrollable.

For all the scientific preparation, the sideshows and the rumours and the media hype, Dubois’s team briefings have one key message. “We need to stay focused.

“I learned by watching [Emirates Team New Zealand], they really stayed focused on what they had to do. Instead of trying to coach a youth team and create an event with a lot of media, they came in like warriors with one objective: to win. That’s what I want for our team.”

This feature appeared in the December 2017 issue of Yachting World. In the February 2018 feature we take an in-depth look at the new access-all-areas Volvo Ocean Race, amid charges of spying, sexism and team secrets exposed… does the truth hurt? On sale 11 January