Tom Cunliffe introduces an extract from Where the Trade Winds Blow the story of a boys' adventures at sea

Lou Boudreau shipped out of Nova Scotia in the 1950s at five months old in the 98ft schooner Doubloon. His father, Captain Walter Boudreau, was one of the pioneers of the Caribbean charter business. As he grew, young Lou served under his father until he struck out on his own at 17 and joined the Bluenose II, one of the greatest schooners of all time.

His life story reads like every man’s dream of the sea and his book about it, Where the Trade Winds Blow, is a rollercoaster from its early pages on the beach in nappies to its last chapter on the Nova Scotia shore with a family growing under his wise guidance.

Aged 13, Lou and his younger brother were given a 25ft island sloop in which to cut their teeth cruising from Marigot Bay in St Lucia. If you’ve ever sailed between St Lucia and Martinique, you’ll have seen Diamond Rock and perhaps wondered, as I have done, about how anybody could ever get ashore there. Here’s a boy, barely more than a child, telling us how.

The Peggy was our first real ship and we had many adventures in her. The Skipper’s policies regarding our expeditions were clear. We had to file a ‘flight plan’ before departure, and hold to it. From the safe confines of Marigot Bay, we often took day trips to bays and coves along the coast, and mostly went where we had been given permission to go. However, had the Skipper and Mother known just where some of our voyages took us they might have keeled over.

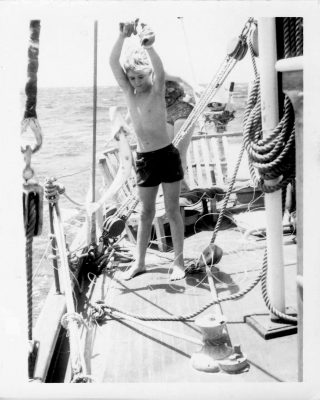

Lou Boudreau grew up around boats and the sea.

When I was 13, we planned an overnight voyage to Pigeon Island. The crew was made up of myself as captain, my brother Peter as mate, and one of my dad’s crew Lewis as deckhand. Stocking the Peggy with a container of Mother’s fried chicken, a small plastic pot of her homemade mango chutney, as well as bread and water, we set off on yet another exploit.

It was a fine day. A blue tradewind sky hung overhead, filled with puffy white clouds. A nor-easterly breeze tossed spray over the Peggy’s bow as we laid a course northward from Marigot Bay, and our little boat danced merrily over the waves, dipping her lee rail occasionally. Before we knew it we were miles offshore, and well past the point that Dad had instructed was a safe limit. As I looked to the north, the island of Martinique and Diamond Rock were temptingly close.

“Pete,” I said excitedly, “let’s go to Diamond Rock.”

My brother looked at me with a little uncertainty. He knew the rock was still a long way off, and most definitely out of our bounds. “Do you think it’ll be okay?”’ he asked, although the tone of his voice told me he already knew the answer. Lewis, on the other hand, had no qualms about voicing his uncertainty.

“De deeper de wata, de more dangerous it is,” he said, and launched into a tirade about sea devils and mysterious disappearances, but Pete and I out-voted him.

It was 19 miles across the channel, but we closed the distance rapidly. Diamond Rock lies on the south side of Martinique, and was closer to us than the big French island. The formidable citadel rose precipitously from the sea, growing in size as our little ship approached.

Stone cliffs dotted with black-mouthed caves appeared, and jagged precipices overhung the sea. Suddenly, I felt a stinging sense of uncertainty. Pete and I had seen Diamond Rock from the decks of our father’s schooners many times, but now it was different. Alone, our confidence waned.

Near the rock massive pinnacles ascended from the dark blue depths to only a few feet below the surface, reaching toward our keel.

We sailed closer, however, until we were a couple of hundred feet off. The stone massif towered over us.

“That’s a big rock, man,”’ Pete breathed.

“Yeah. Let’s go and explore it,” I suggested, with false bravado, “You know, this is where all those soldiers died. Right up there.”

Lewis didn’t let that go by. “You crazy man? You mean it have dead people?” he asked incredulously.

Feat of seamanship

I convinced him they were indeed dead, and had been for quite some time, and although I’d failed to quell my own secret fears, I managed to quell his.

My father had told us the tragic tale of Diamond Rock: “Years ago, when the British and the French were fighting over the islands, a terrible thing happened here. The main port for French warships making landfall in Martinique is just around the corner in Fort de France.

Lou Boudreau with his mother and father aboard a Baltimore clipper ship.

The British Admirals thought that if they could keep the French ships from sailing close in as they approached from the east, they would have to stand offshore, ending up far to leeward of Fort de France.

“The ships were square rigged, and didn’t sail into the wind very well. They could lose days tacking back up into Fort de France. The British decided to put cannons on Diamond Rock to keep the French warships offshore.

It was one of history’s great feats of seamanship and engineering. The British sailed a frigate up to the rock, moored her there, and hoisted the heavy cannons to the top. They built a rain catchment, fortifications, and quarters for the men to live in. When it was all done, the British put a garrison ashore and called the fort HMS Diamond Rock.

“At first, the plan worked well; whenever a French ship tried to sail in under the coast towards Fort de France, the British guns drove it offshore. However, the success was short-lived. The French had been busy, too, and they brought bigger guns to bear from the hills of Martinique, preventing the British frigates from supplying the rock.

Time passed and drought prevailed. Food was scarce on the rock, and the fair-skinned British suffered terribly in the heat. They succumbed to thirst and starvation, yet the Union Jack continued to wave from the heights. To this day, when Her Majesty’s warships pass by, they dip their flag in salute to the men who perished there.”

As I thought about my father’s story, Pete came up with a plan to moor the Peggy, suggesting we drop anchor and take a line ashore at the base of the rock.

“We all go dead, you know dat?” Lewis said.

“Don’t worry, Lewis,” Pete piped in with renewed levity, “it’ll be good fun.”

We dropped the jib and sailed our little sloop up to a point in the calmest lee of HMS Diamond Rock. Pete dropped the main and Lewis pitched the little Danforth anchor overboard. It took hold in the rocky bottom, and as we furled the sails the eerie silence seemed haunting. The immensity of the rock, if not our tryst, now fully dawned upon me.

Lewis gave a big snort and dove in with the stern line. Swimming ashore, he climbed onto a small stone ledge at the water’s edge. It looked as though it was carved in the rock on purpose, for use as a landing point, perhaps. Lewis tied the line around an outcrop of stone, and we hauled our stern in close. Pete and I went ashore as well, but no amount of talking would keep Lewis on the rock. He scrambled back aboard the Peggy the first chance he got, and positioned himself firmly in the hatchway, where he nibbled hungrily on a chicken drumstick, watching from a safe distance. If he was about to die at the hands of some sort of devil on the rock, he wasn’t going without some of Ma Boudreau’s chicken first.

The sun was hot as Pete and I began following the ascension of a perilous stone-strewn path. The rock was barren, with only a few prickly cactus plants and dry sandy earth. It was obvious that little rain fell here. A few lizards scurried out of our way, and huge sea birds followed us upwards, diving and screaming. It was as if they were telling us we had no right to put our feet on this, a place of bravery and suffering long past.

“Hey, Lou, come and see this,” Pete shouted.

He was bending over a bush on the side of the path. Stooping down beside him, I brushed away the dry sand from a long piece of rusted metal.

“It’s a gun!” Pete exclaimed.

A story becomes real

He reverently picked up the old musket rifle and shook away the years of sand that covered it. His treasure was held in the hands of man for the first time in more than a hundred years. He held it as if to fire it, and sighted along the barrel. The wood had long since gone, but at that moment it was real enough to us.

The formidable Diamond Rock south of Martinique

We climbed further before coming to the area where the soldiers had lived and died. An old stone cistern and living quarters had been built into the side of the rock. We found many treasures that day. There were brass sword hilts with heavily rusted steel blades and pistol barrels with the flintlock firing mechanisms, and white leather straps from uniforms, preserved by the dry sand and hot sun. We collected dozens of musket balls and a few cannon balls. There were scores of these, but because of their weight we could not carry many. I found some brass buttons from officers’ tunics, and a long-stemmed white clay pipe.

As I stood there in the ramparts of HMS Diamond Rock, with a rusty pistol in one hand and the remnants of a sword in the other, I felt a strange sensation come over me, as if there were indeed ghosts here. I closed my eyes for a moment and saw the soldiers then, in their red tunics with white straps, standing in the sun. Peter shook me out of my daydream.

“Look down there, Lou.”

I looked downwards to where Pete was pointing. From where we stood, our sloop looked like a tiny red dot on the water next to the base of the cliff. The sun was halfway down the sky, and Lewis was waving from the safety of the hatch. It was time for us to go, and we scampered down the rocky pathway to the landing.

Lou and his two brothers playing in a ship’s longboat on deck

It wasn’t long before we were on our way again, the little red sloop’s mainsail filled and her jib bellied out to catch the wind. Once clear of the big rock, the Peggy heeled to the steady easterly breeze, bound for Pigeon Island, which we could see some 20 miles distant.

There had been much during the day that was new to us, and another new experience was soon to come. Although we had done a lot of sailing by then, we always planned to be anchored at night. Now, as the last rays of light from the setting sun died to the west, I felt very alone on the greatness of the sea.

It would be completely dark soon and we were far from land. The Peggy had no compass or lights, and Lewis had eaten all the chicken while we were ashore. Pete steered, and as the completeness of tropical darkness fell down upon us, the stars came out in their millions, dotting the sky in an impossible array of splendour. We soon saw the glow of Castries town, and steered our course accordingly.

The wind turned light and our little sloop glided slowly across the Martinique channel. Pete and I talked through the night with the stars as our guide. We talked about the fish, the birds, and the sea as the warm Caribbean gurgled beneath our keel.

The Peggy anchored in Pigeon Island as the sun rose. After resting the morning, we set sail again to make the final passage down the coast to our home anchorage of Marigot Bay. Our story was that we’d found the artefacts on the other side of Pigeon Island.

“Amazing,” the Skipper said, his brow furrowed…

If you enjoyed this….

If you enjoyed this….

Yachting World is the world’s leading magazine for bluewater cruisers and offshore sailors. Every month we have inspirational adventures and practical features to help you realise your sailing dreams.Build your knowledge with a subscription delivered to your door. See our latest offers and save at least 30% off the cover price.