Line handling is an essential skill for keeping yourself and others safe but how best to go about it? Rachel Sprot reports

Boats may have nine lives, but a sailor is not supposed to have nine fingers. Every year, however, we hear of instances of crushed hands, lost fingers, and major damage from poor line handling techniques. Technological advances have greatly reduced the amount of sail and line handling required of today’s sailors.

Sail areas are increasingly concentrated in a few, large sails, rather than broken up into several smaller ones. Hydraulic furlers, asymmetric spinnakers, in-mast reefing and self-tacking headsails all mean that we need less rope to manage our sails.

If you’re in a hurry, running your hand along the length of a line can help avoid kinks. Photo: 59° North Sailing

In fact, rope is notable in its absence from the sleek cockpits of new yachts, which can often seem like a lines-free area.

The risk of this is that out of sight can mean out of mind and, while the amount of line handling on modern yachts has decreased, the loads on those remaining lines has not.

Line handling is an essential skill for keeping yourself, and others, safe. As skippers, it’s something we should be talking about more often, especially whenever we have novice crew on board.

I asked other sailors for their thoughts and was surprised by the strength of their responses: everyone had a story to tell.

Respecting the loads

“A loaded line”, the former skipper of the 125ft Fife Mariquita, Jim Thom told me, “is like a loaded gun. They’re silent until they go off.”

It reminded me of an incident aboard an 80ft maxi I’d once worked on as a deckhand. The genoa sheet blew without warning, and it did, indeed, sound as though we were under fire.

Ensuring you don’t raise the line above winch level is key to preventing the line from spinning off. Photo: Yachting World

The sail flogged violently until we tacked and took on the other sheet. Fortunately, no one was on the leeward side deck at the time.

The speed and ferocity with which it happened have stayed with me and to this day I’m never comfortable with anyone standing near loaded lines.

Understand the power when line handling

A winch magnifies your effort by whatever ratio they’re designed for.

A modest 50:1 winch will output 1,250kg to the line for the 25kg you (or the batteries) apply to it.

That’s about the same as the weight of a VW Golf which, if it was actually attached to the other end of your halyard rather than the mainsail, would certainly focus the mind.

Novice crew won’t know how much pressure to apply to a winch and will need supervision.

experienced sailors transitioning to larger boats may not understand the loads involved and overexuberance with a winch can prove catastrophic.

One cruising sailor, who had decided to charter a larger than normal yacht in the Med, applied their beginning of holiday joie-de-vivre to a halyard winch and brought the mast down, somewhat curtailing their charter.

Winch technique

Winch handling technique needs to be revisited as the size of yacht you are sailing increases. Inexperienced crew need detailed winch briefings and demonstrations.

Standing sideways onto a winch with hands in a closed fist, little finger towards the load, gives the strongest stance. Three turns should be sufficient for pulling in by hand, anymore and you risk getting a riding turn.

However, extra turns are needed before tensioning it. A common mistake is to only use three turns and then go straight to the self-tailer.

Filling the winch drum with four or five turns is a critical moment when accidents can happen – keep hands well away. Photo: Rachel Sprot

While the self-tailer may grip the line enough to apply considerable load to the line, at some point it may need easing and will need to be taken out of the self tailer, with insufficient turns on the drum to manage the now considerable load.

Filling up the drum with four or five turns is a critical moment when accidents can happen. Crew should be briefed to slide their hands down the line, keeping them a safe distance away from the drum as they do so.

Keeping hands well back from the winch when line handling gives more thinking time if it does slip. Working at winch height, and not raising the line above winch level, is key to preventing the line from spinning off.

Handling a loaded winch with insufficient turns is dangerous.

Those lines not being used can then be coiled neatly on the guardwires. Photo: Rachel Sprot

One skipper of a 70ft yacht reported losing their hearing for a week after they were hit by a flogging jib sheet. They’d stepped in when a novice crewmember, who had only applied two turns around the drum, was struggling to keep control of the line.

Having long tails on the headsail sheets means that if they are flogging an extra turn can be lassoed on without getting too close to the winch. Headsail sheets which are only just long enough for normal operation, will be too short to do this safely.

Deck gear

Lines are only as strong as the things they’re attached to. On a boat which is working hard there’s nearly always something working loose, or seizing up.

Doing a deck walk and keeping a simple set of tools handy to rectify any defects, such as seizing a shackle or tightening up a car assembly, are easy to do and may prevent a more serious failure.

Knowing what lies underneath your deck fittings is also important: are there substantial backing plates, or just a few penny washers?

Gear failure is often preventable if signs of fatigue are identified early on, and the equipment is used as it was intended.

Flaking a line

As boats get larger the lines don’t just become thicker, they also get longer. The longer the line the more difficult it is to work with.

your hand along its entire length will help take out any kinks, and if you’re in a hurry, can be just as effective as flaking it into a perfect figure of eight (though don’t say that out loud in St Tropez!).

Flaking a braided line into a figure of eight will help prevent kinks that could hinder line handling. Photo: Rachel Sprot

Stopper knots

As the line diameter increases, the figure of eight becomes less effective as a stopper knot: they shake loose too easily. An Admiralty Stopper knot is more secure.

Danger zones

Be aware of apex zones, such as a preventer line doubling back around a block on the foredeck. If the block failed, anyone standing in the apex could be seriously injured.

Ideally, we should avoid creating an apex in the first place, especially if they rely on a single component like a block. It’s better to run a preventer through the fairlead, or around a bow cleat, in addition to any blocks.

Article continues below…

5 expert tips: How to improve your offshore racing skills

French Figaro sailors, whether they’re currently on the circuit or former Figaro skippers who cut their teeth in the class…

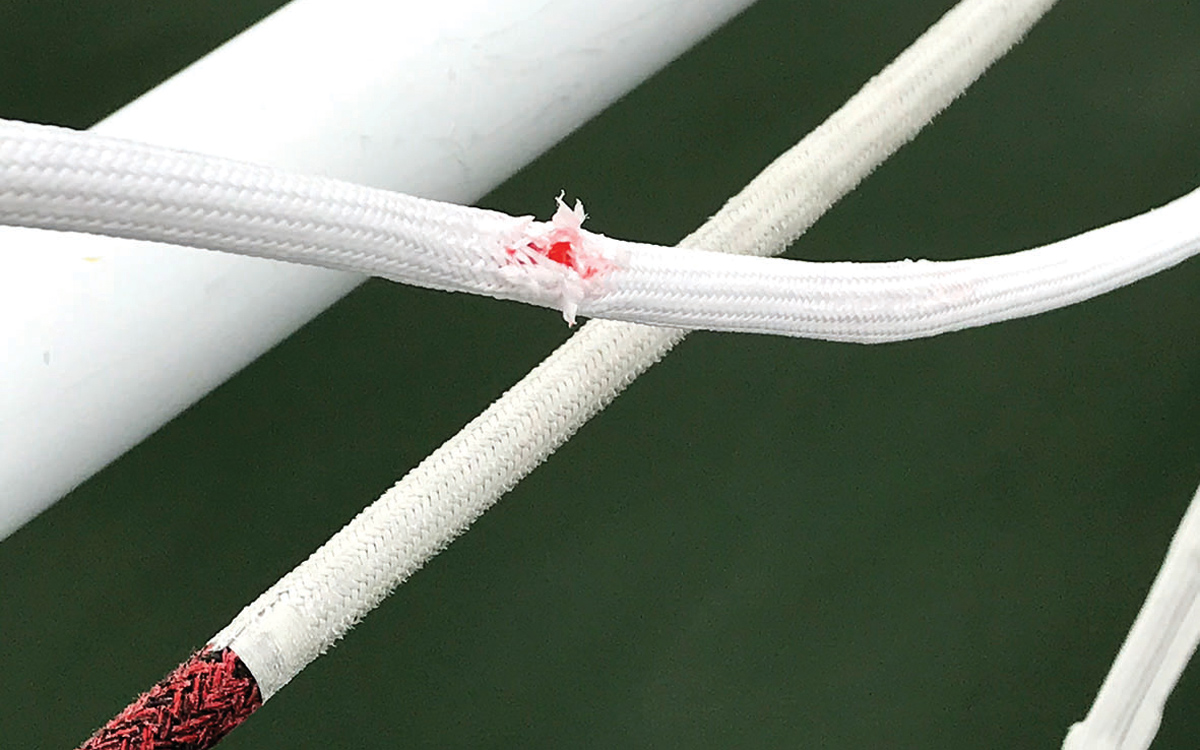

Pip Hare’s top tips for preventing chafe on lines, sails and hardware

Chafe on sails and ropes is something we should expect as part of the general wear and tear on passage,…

Let go

When line handling becomes a tug of war it’s time to let go.

Amy Graydon, first mate of a sail training vessel, explicitly teaches that ‘let go’ means open your hands and drop the rope after a crewmember suffered a rope burn from trying to hold a headsail sheet which didn’t have enough turns around the winch.

Tidy up

Loose lines on deck are dangerous: they’re a trip hazard, won’t run freely when they need to be eased, or run too freely and end up in the water.

A messy deck disguises hazards such as a bight of rope, and will make it harder for crew who are quite literally learning the ropes, to see what’s going on.

A thumb knot in the block secures lines not currently in use. Photo: Rachel Sprot

The tails of lines in use should be coiled around the winch they’re associated with or flaked neatly beside them. Lines which aren’t in use, such as spinnaker sheets, can be coiled on the guardwires and secured with a thumb knot in the block.

And without going into full Marie Kondo mode, there’s something very satisfying about a row of well-stowed halyards!

Stay calm

Line handling often occurs at high pressure moments: coming alongside, spinnaker hoists, a sudden tack. These are all times when the skipper might be feeling stressed, and it transfers to the crew. Take your time for manoeuvres and make time for line handling.

Calm leadership will prevent people from making mistakes and enable them to perform at their best.

If you enjoyed this….

If you enjoyed this….

Yachting World is the world’s leading magazine for bluewater cruisers and offshore sailors. Every month we have inspirational adventures and practical features to help you realise your sailing dreams.Build your knowledge with a subscription delivered to your door. See our latest offers and save at least 30% off the cover price.