Jonty Sherwill asks yacht racing veteran Peter Morton for his top tips on how to survive a squall

Things get complicated when dark clouds build to windward and the horizon looks more like night than day. There’s breeze under squall clouds, but could it herald a major change in the weather? Can you survive with the sailplan or should you change down?

While you may be fine under current conditions, doing nothing risks blowing out sails or could end your race completely. But to change down jibs or drop the spinnaker might lose you the race. It’s a gamble, but delaying the call until the boats around you are on their beam-ends is probably far too late.

When the squall arrives, how you deal with it will depend on the boat you’re sailing. Dayboat sailors with all-purpose sails have few options, but those on larger boats can rue an expensive mistake if they have the wrong headsail or spinnaker up. It’s also easy to underestimate the effects of windchill. A shivering crew in a rising wind will soon lose concentration, so have foulweather clothing to hand below decks.

While the helmsman and trimmers are looking after the sails, the navigator and tactician need to be looking ahead to decide how to come through this blow with the boat intact and ahead of the pack.

1. Anticipation

You’ll often see a squall coming towards you as heavy rain and/or a big cloud build-up. The main priority is to consider the crew and boat safety. If you are near a lee shore try and get as much sea room as possible – while the boat may well survive without a rig for some time it won’t fare well washed up on a beach or rocks.

Try to assess if this is a short ‘one-off’ squall under a cloud or a weather system change, which might herald a series of big gusts or a permanent windshift. Either way you need to get to the inside of the expected shift.

2. Talk to your crew

Discuss your sail changes and priorities in advance: would you go to a smaller jib or reef first, or would you simply drop the jib and reef the main if the squall were that bad? Make sure the sail of choice is close to hand below.

It is vital to maintain steerage, so unless the conditions are extreme, dropping the sails completely is not a great idea. If it gets really bad and you do have to motor, remember to check for sheets and guys overboard before you put the engine into gear.

3. Don’t allow sails to flog

There’s a bit of a misconception that the choice of upwind sail is paramount on big boats. The main thing is not to allow sails to flog themselves to death – apart from costing you money, it’s difficult to control the boat when the sails are out of control.

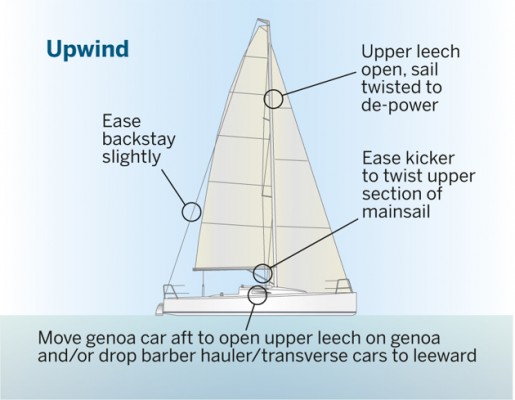

Move the jib cars back to keep the foot sheeted, but the top twisted and if you have athwartships tracks, drop the cars down. This is better than easing sheets, which tends to make headsails fuller – not what you want in strong breezes.

The main should also be twisted with the kicker eased, but without letting it flog, and it’s worth easing the backstay to reduce the loads and the bend in the rig.

4. Sailing downwind

A squall while sailing downwind is always tricky. To some extent your tactics will depend on the type of boat; modern boats such as TP52s tend to go faster as they sail pretty close to the wind speed until it gets extreme. If it is a huge squall, take down the spinnaker. Otherwise, be aware that this ploy can reduce speed so dramatically the boat becomes harder to handle.

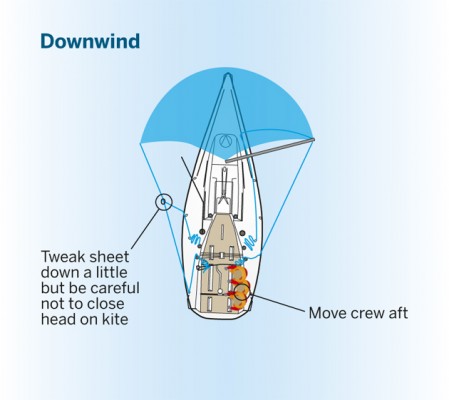

True wind angle is the key here. If you can hang onto the spinnaker, the trick is not to sail so deep that you risk a Chinese gybe, but not so high that you risk a broach. Move the crew right aft and tweak the sheet down a little, but not so much as to close down the head of the kite.

If you do spin out, the best thing to do is to keep the sheets and guys on, but to blow the halyard (though not completely) – that will keep the kite close to the boat, but not under the boat.

5. Inshore v offshore squalls

I don’t think there is a huge difference between dealing with squalls inshore and offshore except that you will have more sea room offshore, which from a racing perspective means you have more time to recover.

The main thing is to look after the boat – ensure you are in a position to continue the race even though in the short term you may have been a little over-cautious.

Peter Morton is probably best known for reviving the Quarter Ton Class in Cowes with his wife, Louise. But his 30 years of Solent and offshore racing includes wins in the Quarter Ton World Championship with Graham Walker’s Indulgence in 1986, the Admiral’s Cup, the Commodores’ Cup (twice) and the Fastnet Race.