Jonty Sherwill asked sailmaking guru Peter Kay for his top tips on mainsail trimming

“More speed!” is the call from the weather rail. The helmsman is telling you he’s got too much helm and all eyes are on the mainsheet trimmer to sort the issue.

With other boats close by swift action is needed to get the boat back on her feet and driving forward before she slips backwards into the fleet.

Doing a decent job of mainsail trimming is crucial to your team’s performance and, while it can be a pleasurable workout on a small boat, juggling tactical duties with playing backstay, traveller and mainsail twist, move up to a 50-footer and the task gets a whole lot tougher, even though the job list might look a bit shorter.

Either way it’s a multi-task role and acquiring a good feel for the boat in all modes and sail configurations can take more than a few races.

Although modern, light cruiser-racers will need depowering early, heavier displacement boats will carry a fully trimmed mainsail further up the wind range.

Logging the effect of alterations to rig tension and an accurate set of target boat speeds will help the mainsail trimmer, but establishing a good rapport with the helmsman and headsail trimmers should fast track you to delivering the performance the guys on the rail are looking for.

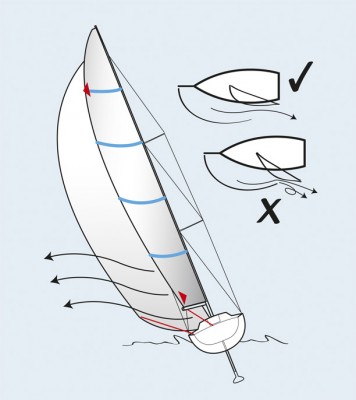

1. Power reaching

This is where well co-ordinated trimming counts, especially with a big asymmetric. If the next waypoint is higher than you’d like, putting you on the edge of control, then for maximum speed keep all load off the mainsail leech, but don’t just dump it down the traveller and into the airflow off the A-sail leech. The A-sail also needs to be trimmed as twisted as possible – assuming tweakers are used – but the main traveller can be kept high with the sheet and vang trimmed on to keep the main from flogging.

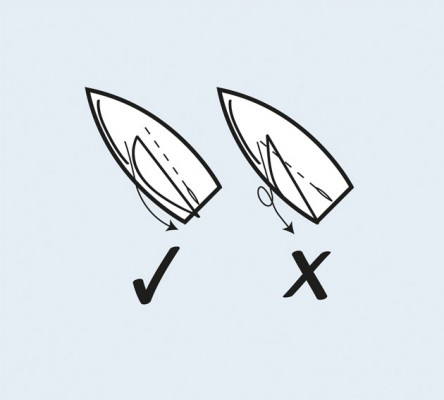

2. Surviving the gybe

In a light boat with good sails it’s fine to flick the boom across mid-gybe while steering to keep hull under rig, but in a bigger yacht in a breeze this is a high-risk manoeuvre. High-tech sails age and lose their strength and unless there’s a good reason to ‘throw’ the gybe, I always endeavour to sheet the sail at least halfway in, so there’s less shock load on the leech as it flies across. It’s notable how often tired sails break in a slow, innocuous gybe, when low boat speed increases the apparent wind speed and shock load.

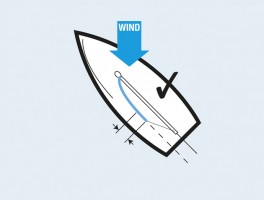

3. Match the pressure

Always aim for a flat foot tempered by the need to get depth and power higher up in the sail. There’s not much point in creating a large pressure differential just above the boom because the air will be drawn down under the boom, creating a drag-increasing vortex that will only slow you down. As the breeze builds you should progressively flatten the main with backstay and luff tension to allow sufficient tension in the leech without generating heeling moment. Too much backstay applied with a soft mast will cause the mainsail to flog.

4. Dealing with gusts

There are two basic philosophies, dinghy style with the traveller down, or my preference of keeping the traveller high – no more than 20cm down off the centreline. Keep the sail bladed with backstay as necessary, but ease the sheet in excessive puffs. This way power comes off at the top first and some load is kept on the lower leech to keep the helm loaded so pointing is retained. In extremis, dump the traveller quickly, but get it back up as soon as possible.

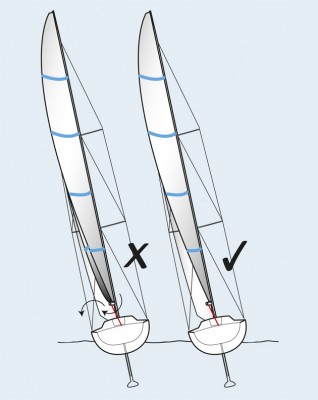

5. Speed and height

Try setting the aft 30cm of the top batten parallel to the boom when viewed from below. Then set the boom on the centreline by looking aft and comparing its position on the centreline to the backstay. This guide works up to where the sail plan is generating maximum righting moment, even though the main has been flattened as much as possible. Beyond this point more twist is needed to keep the boat on her feet.

Extra pointing is achieved by trimming harder, ie hooking the back end of the top batten to windward and pulling the boom marginally above the centreline. Use the technique cautiously when the tactical situation requires it and be aware this will increase side loading on the keel, creating more drag. Boat speed will suffer, so keep a close eye on it and gauge when to come back down to a fast forward setting before returning to a high mode if necessary.

Peter Kay was chief designer at North Sails UK in the 1980s and was involved in three America’s Cups. He started Parker & Kay Sailmakers in 1989, later associating the business with Quantum and latterly OneSails. As a sailor, he has won national titles in Snipe and OK Dinghy classes, as well as European and World titles in 6-metres and Swans.

This is an extract from a feature in Yachting World April 2015