Battling severe weather in an ice field, the crew are floored when the schooner Bowdoin dives beneath a freezing wave. Tom Cunliffe introduces this extract from I married an Explorer

Today, the auxiliary schooner Bowdoin operates under the flag of the Maine Maritime Academy, making training runs to Labrador and Greenland. Launched in 1921, the 66-ton Bowdoin was the brainchild of Donald (Mac) MacMillan, an explorer of the far north.

Specifically built for the Arctic at 88ft x 21ft, she is double-planked and double-framed in oak, beefed up at the waterline with a 5ft belt of 1½in greenheart. Her rudder is extra-large for manoeuvring in ice, her propeller is super-deep and the hull sections are rounded to rise up when nipped in ice.

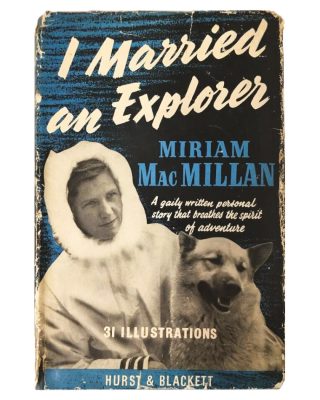

Mac knew exactly what he was about, but for most of us he might have remained obscure but for the book his wife wrote in the 1930s about voyaging with him and his crew to north-west Greenland. Miriam MacMillan’s I married an Explorer is long out of print but well worth chasing down. In this extract, she describes how Mac works the Bowdoin through a potentially disastrous ice situation to see the ship safely home.

When we left the village behind, a dozen Eskimos (sic) escorted us out of the harbour in their kayaks, their silver wakes speckled with sunlight as they skimmed gracefully over a perfectly calm sea.

When we left the village behind, a dozen Eskimos (sic) escorted us out of the harbour in their kayaks, their silver wakes speckled with sunlight as they skimmed gracefully over a perfectly calm sea.

Unable at last to keep up with our gathering speed, they ceased their efforts and, resting on their paddles, waved and shouted until we were well on our course. We watched these swarthy hunters of the North as they turned about and slowly paddled away.

After they had turned toward home they never looked back. I thought of Mac sailing away from me in the Thebaud before we were married. He never looked back, either. Was this a habit bred by some mysterious influence of the north, I wondered?

The following morning, a chilly outlook greeted me when I stepped on deck although it was the middle of August. The cause lay directly ahead – an ice field of tremendous proportions. Mac estimated that it reached out from Baffin Land for at least a hundred miles, completely blocking our route home.

For hours we zigzagged in search of a good lead. “If this wind hauls to the east,” said Mac drily, “it’ll divide the pack in two.” I knew what that meant. We could easily be caught between the two great sections and carried off wherever Old Torngak, the Evil Spirit of the North, cared to take us. Hundreds of ships had been destroyed there in September and October gales.

With no radio, lighthouses or fog-horns for hundreds of miles around, and only a few seals and two huge finback whales to entertain us, we felt awfully alone. “That whale is as long as the Bowdoin,” said Don, when a tremendous black body bulged out of water. The second time it came up it was close enough to the ship for us to see that it was nearly as long as the Bowdoin, 70 feet at least.

But the ice field concerned us more than any whale. Like a great octopus, those icy arms tightened round, holding us firmly. Ice pans large enough to carry our crew down through Baffin Bay jostled us on all sides. For flatness, size and smoothness we could have our choice.

One classic drift of a lonely ship took place at Cape Dyer, not so far from where we were at the moment. In 1854, the Resolute, one of those Franklin search ships, became locked in the ice. She was abandoned in Barrows Straits about 75° North Latitude.

Before leaving the ship the men had put everything in order; the rudder had been taken on board and every movable thing packed away below or securely lashed on deck. One year and four months later the Resolute was sighted in the ice pack off Cape Mercy near Cumberland Sound, in 67° North Latitude. She had drifted out through Lancaster Sound, and on down Baffin Bay, a distance of 1,200 miles in 16 months.

A crew was put on board which brought her safely back to New London, Connecticut, where Congress rewarded the captain and his crew with 40,000 dollars. Eventually, the Resolute was repaired and returned to the English Government as a token of national goodwill.

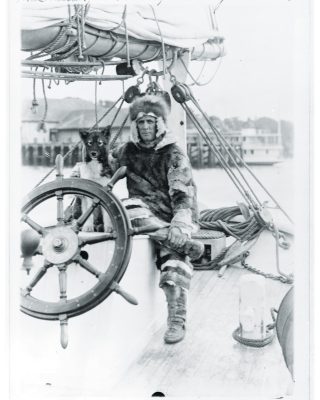

Arctic explorer Donald (Mac) MacMillan at Bowdoin’s. Photo: Library of Congress/Corbis/VCG via Getty

wheel and well wrapped up against the cold

With so little fuel oil left, we ourselves were fast getting back to the 1850 days when ships relied entirely upon sail. I wondered if someone someday would look down from the air and say, ‘That’s where the Bowdoin was crushed in the ice over a hundred years ago. The crew drifted south on an ice pan.’ The very thought of it gave me the chills.

For the next three days we played hide-and-seek with the pack. At times it was blinding white under the direct rays of the sun. Again, layers of low-lying mist shut it out completely. Every variety of weather hit us during those three uncertain days – snow squalls, rain, fog, shifting winds. And always the ice pack ahead and icebergs all about.

That third night Mac came wearily down from the observation barrel aloft and said, “Get out the ice anchor, Harold, we’ll tie up to a pan until we can see a lead. Nothing in sight now. Wind’s shifting to the east’ard and I don’t like it.”

A large flat ice pan made a good dock. Then, leaving orders for a continuous watch, he went below to snatch some sleep, only to pop up every few minutes for another look at the weather.

A couple of hours later he was climbing the rigging once more. Finally, came a call: “Get in the anchor, give ‘er the engine.” And again we began worming our way through the pack. After some time George went into the rigging. “Land off the port bow, sir,” he shouted with the confidence of a Columbus.

“Greenland,” Mac answered through the megaphone. He’d seen it himself long before. “What!” I exclaimed. “Why, we’ve been sailing away from Greenland for three days.” But we couldn’t mistake those icy snow-capped hills.

Our trailing log line had been no help to us in the ice and we had long since hauled it aboard. So it was impossible to tell our progress south, east or west. Our frequent detours would have made the log worthless, anyhow. Nor had the weather allowed us to take sights of longitude or latitude. But Mac’s mind was made up on one thing. We’d get out of this pack somehow, even if we landed back in Greenland.

Anchored to ice

After a while the ice pack thinned out a little and things looked somewhat brighter for a moment. But now our water supply had finally reached a dangerous low. For some time we had abandoned any desire to bathe in the precious liquid, but we did crave a drink now and then. This meant finding a berg and filling the tanks. What more could one want than a big swallow of an iceberg – a drink made from snowflakes which fell perhaps ten centuries ago.

Mac selected a huge berg with a flat projecting shelf and, without using the engine, sailed the Bowdoin alongside as gracefully as though it were a dock in Maine. Over went the ice anchor, jabbing into the berg and binding us to its side. Then over went the crew, as anxious to stretch their legs by running somewhere as to get a drink.

It was dip and hoist, dip and hoist, as water cans swung back and forth over the rail. Within an hour all tanks and containers were filled, but now that we were securely tied to a berg, why not make the most of this temporary security and get a good sleep?

Mac was decidedly fagged. No one else on board understood ice navigation and the responsibility for getting us safely through the ice pack was all his. The fact that he’d remained on deck almost constantly was proof to me that the situation was serious. So, setting an anchor watch, Mac and the rest of us turned in.

Old Tomgak, however, hadn’t finished with us yet. We had hardly settled down when there came sudden grinding, crunching noises against and under the ship near the propeller. Mac rushed on deck, gave a quick look and snapped out two orders: “Take in the ice anchor and start the engine.”

Indigenous Greenlanders aboard Bowdoin in 1923. Photo: Bettmann/Getty

Just as we backed away, a tremendous chunk dropped off our iceberg with a mighty splash and not long afterwards the entire lower shelf to which we had anchored broke loose and drifted away.

The barometer fell rapidly and the wind hauled dead ahead. Rough weather is one thing, but when combined with ‘slob’ ice and icebergs, the picture takes on actual danger.

There was nothing to do, though, but push ahead. Under jumbo (fore staysail), foresail and trysail, we ploughed on southward against increasing blasts and a villainous sea, the bow of the Bowdoin battering pan after pan and at times going completely under. Mac stood well forward and I wondered how he managed to keep his feet. Clutching the after rail, with one eye on Mac, I was listening to the whistling of the wind, the swishing of the sea and the crunching of the ice.

Nosedive

All at once our bow completely disappeared and Mac with it. The impact, which brought the Bowdoin to a complete stop, pitched me headfirst into a row of oil barrels and knocked me out for several minutes. My last recollection was seeing Mac going down with the ship.

When I finally came to, my first thought was of him. The bow was still there but he wasn’t. Then I looked aft as if to catch a last glimpse of him floating by and my eye fell on a figure in oilskins clutching the wheel. It was Mac.

Bowdoin in Greenland, 1923. Photo: Bettmann/Getty

He didn’t even see me. Nor did any of the rest of the crew. They were dashing madly up and down the for’ard companionway, dumping pails of water into the sea. I was still hazy. Had we attempted a submarine act and filled the for’ard cabin? Or was there a fire below? If so, the boys were certainly going in the wrong direction with the water.

I got the story piecemeal. It seemed that Mac had grabbed a halyard as he was being literally swept off his feet. When he came up out of the plunge, realising what had happened, he’d rushed aft to take the wheel while all the rest of the crew bailed out the fo’c’sle.

The plunge of the ship which sent me whirling headlong down the deck caused considerable other damage. For just before the collision one of the boys had opened the sliding hatch leading to the fo’c’sle. As he started down the ladder there came the complete submerging of our bow.

Water poured below like a cloudburst, washing him down the ladder and flooding the cabin. The deluge put out the galley stove, drenched everyone standing near the companionway, and even uplifted floor boards under which we had stowed much of our foodstuffs. It was a rush to rescue the flour, cereals, sugar, puddings, in fact everything wrapped in cardboard boxes.

Seafarer and author, Miriam MacMillan. Photo: Library of Congress/Corbis/VCG via Getty

Our deck pumps aft near the mainmast couldn’t reach this for’ard water and it couldn’t flow aft because the limber holes were plugged with coal dust. So nothing to do but bail it out of the bilges by the slow process of pail by pail. The combination of odours-choking bilge water and fumes from the galley stove proved too much for some of the boys. Several, who hadn’t felt the slightest seasickness up to that point, when they reached the rail, emptied not only pails of water but their stomachs as well.

Drying out

Nobody forgot that plunge for a long time. It was many hours before the galley stove would burn again to dry out the fo’c’sle and heat coffee. Much of our remaining food supply was ruined. But Mac was all right and that was enough for me.

After many hours of grudging use of our fast diminishing fuel, the ice field faded behind and we stopped the engine and laid to under trysail. This helped somewhat to decrease the amount of water coming over the rail for’ard.

Somehow we got through it. At the end of seven days, there before us was Labrador, the four jagged peaks of Cape Mugford welcoming us back. Down went the anchor. The dinner bell rang. Starboard watch (lucky ones) all dashed below. Mac spoke quietly to me and a lad who was still on deck.

“Better be glad we’re here and not out in the ice pack. Remember that night we tied up to the ice pan and the wind shifted easterly? Things looked bad,” he admitted, willing enough to explain, once the danger had passed. “We could easily be there right now. Perhaps for all winter.”

I thought there had been some good reason for his heading toward Greenland that night, determined to work out of the ice field at all hazards. Now I understood.

If you enjoyed this….

If you enjoyed this….

Yachting World is the world’s leading magazine for bluewater cruisers and offshore sailors. Every month we have inspirational adventures and practical features to help you realise your sailing dreams.Build your knowledge with a subscription delivered to your door. See our latest offers and save at least 30% off the cover price.