The wrecking of Volvo Ocean Race crew Team Vestas Wind on remote reef is a reminder of the chief danger of modern electronics - the illusion of faithful accuracy

How is it possible for a yacht bristling with the latest technology to hit a well-known reef, as Volvo Ocean Race crew Team Vestas Wind did, with catastrophic consequences? How can it happen to one of the world’s top navigators?

And if they can make a mistake, as skipper Chris Nicholson has manfully admitted, can we observers really say we wouldn’t make the same one ourselves? Never?

It’s all too easy to see how this might have happened, and anyone who has ever sailed in the poorly charted, reef-scattered tracts of the Pacific or the Indian Oceans can imagine why and how. It would be bad luck and arrogance indeed to sit in judgment and say no, not me, it could never happen to me.

This is not like coastal navigation in Europe. To sail in remote areas of the world is to go back in time, and the disaster of Team Vestas is a collision in more senses than one: a collision of the modern and minutely known world, crawled to centimetres from the deeps of bathymetry to the prying exactitude of Google Streetview, with a surprisingly vast oceanic landscape that remains a best guess estimate.

Despite all the modern technology available this is an old-fashioned shipwreck, such as have splintered ashore in every age and done for countless mariners over the millennia. They found themselves stranded ashore, in a place without habitation, water, food or communications, a predicament straight out of Robinson Crusoe, but with journalists as far away as another galaxy incongruously and futilely clamouring for photos and interviews.

As for why this happened, my guess is almost certainly for the same age-old reason: the crew were sure they were where they were not.

Even today, this is easier than you might think. Modern charting seems so accurate. And so often it is, as when the dot on your chart plotter puts you alongside your very marina berth. This precision makes it surprisingly hard for the brain to shake off the idea of that picture as fact. We can readily accept the idea of a certain margin of inaccuracy, and make routine allowances for it, but half a mile, a mile, five miles?

In many parts of the world, reefs and islands, some like the reef Vestas tore into, are barely rocks awash and well nigh invisible at distance, and they may be a mile or miles from their charted positions. One Pacific atoll is known to be six miles from where it is shown on charts. The information used for charts may still largely be based on leadline surveys from the sailing ship days of the 19th Century.

Satellite imagery has allowed modern hydrographers to work out where many of these islands actually lie, and often an offset is printed on paper charts, though not necessarily reproduced on electronic charts. Many charts of these areas have been corrected to the WGS84 datum, while others have not, and so the position of an island can vary from chart to chart, or at different zoom levels.

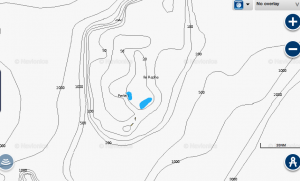

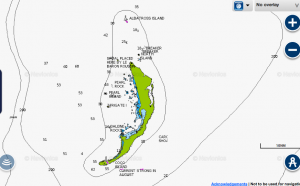

With electronic charts there is also the matter of detail at different zoom levels, which can also be seriously deceptive. An island or reef may appear inconsequential at one zoom level, but resolve into a sizeable hazard a single zoom step in. As an example of this, take a look at these two images from the Navionics web app that shows the reef Vestas hit at one zoom level, then in more detail (and substance) in the next.

Accepting that all charts, electronic and paper, represent an approximate picture and not reality requires a mental recalibration on several fronts, particularly at a speed of 19 knots, as Team Vestas was making at the time of the grounding. At this speed the distance of a 1,000m chart inaccuracy would be covered in under two minutes.

This is not the first time a high-profile race yacht has been shipwrecked on a remote reef. In 2010, the Clipper Ventures yacht Cork hit a reef in the Java Sea and foundered. The circumstances were broadly similar, in that the collision happened in the dark, the reef was remote, uninhabited and low lying (too low to produce a strong radar picture), there was no significant change in the soundings, and when the yacht grounded getting the crew off the boat was dangerous in itself.

The reef the Clipper yacht hit, Gosong Mampango, is 1,000m east of its charted position, and an associated reef to the south is two miles to the north-east of where it was charted. The electronic charts did not carry the warning that the paper charts did that the reef was almost a mile east of its charted position.

What we can perhaps learn from the Team Vestas incident, as with the Clipper shipwreck, is simply more caution. A second system of navigation is needed, be it only soundings, to verify GPS positions. A larger margin of error is needed in areas of suspect charts with, as was recommended in the report into the Clipper grounding, different offlying waypoints for daytime and nighttime approaches.

We would all be safer in these places if we felt the instinctive deep fear of reefs that sailors had in years gone by, when landfall was accepted as the most imperilled part of any passage. But how can we arrange to feel it today, when modern navigation equipment has all but expunged dread of the coast and we are all, mostly, hand on heart, more interested in sending emails and routeing options and getting the latest grib weather files?

Despite all the great benefits of GPS, chart errors, scale errors, and sailors’ errors continue to catch out skippers who think they’d never make these mistakes. They catch out cautious cruising skippers and the world’s best navigators alike. If you sail long enough, far enough, mightn’t anyone have a few close shaves?

When we were in Fiji in July researching and filming our current bluewater series, specifically setting out to show the difficulties of navigating in coral and how to go about it (including entering a coral pass and lagoon that was not even shown on our electronic charts, even at the largest scale) we learned that some dozen yachts a year are wrecked on reefs here, even though most of these reefs are reasonably well marked.

Most round the world sailors don’t put all their faith in charts and today many cruising sailors work out the location of reef passes, islands and lagoons by georeferencing Google Earth images and using them in conjunction with electronic charts. (We have a four-page feature on how to do this and where to get the data and images required in our November issue).

But for all that, even brandishing every known source of information, seamanlike reef navigation depends on the very same techniques that were used in all times gone by: the sun overhead and behind you and someone high up in a conning position applying the Mk 1 eyeball to assess what is really beneath and ahead. And the inclination to use every sense, including sound and feel, and to turn back if uncertain. The biggest danger is certainty.