The bulk of what is known about rogue waves comes from the accounts of survivors, some of whom lost crew members and friends in the experience.

Rogue waves and the Agulhas current

One of the most notorious regions for rogue waves is the southern coast of South Africa where the five-knot west-going Agulhas Current meets strong westerlies from the Southern Ocean.

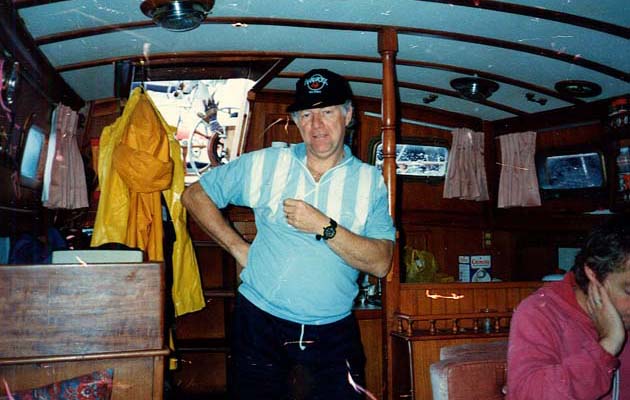

Rod Briggs recalls what happened to him there on the 40ft Vyndi in the 1990s: “The day dawned bright and sunny onboard Vyndi, which Peter Atkinson and I, as skipper and watch captain, were delivering to Durban. Also on board were the owner, Rob Upton, and a friend of mine, Errol Breen.

“We had left Cape Town three days earlier on a routine trip to Durban and had been under motor for a few hours. Although the sea was calm there was a severe swell running, indicating heavy weather below us in the Roaring Forties.

“Southern Ocean storms are very common but something about the set of this swell disturbed both Peter and me and caused us to re-evaluate our sailing plan.

“A couple of hours under motor brought us in sight of Knysna, a picturesque town on a lagoon, guarded by two sheer cliffs known as the Heads. Between the Heads is a narrow channel, navigable but dangerous due to the surf line, which regularly breaks right across the entrance.

“Pete and I had sailed through the Heads many times and followed our usual practice of waiting offshore while we discerned the pattern in the surf and timed the wave interval. We noticed that every third wave met with the Southern Ocean swell, causing the surf line to break right across the entrance.

“Faced with the dilemma of crossing a dangerous bar or carrying on in a very strange sea state we decided to call for the latest maritime forecast. The lifeboat base at Knysna relayed the following: ‘Light to moderate S to SW winds from 1800.’

“As this was the perfect wind for our journey, giving us a broad reach up the coast, we unanimously decided to carry on. By nightfall we were in a full gale.

“As three of the four of us on board were very experienced yachtsmen the gale did not worry us. It was unpleasant, wet and wild but with a well-found vessel should not have been life threatening. While Pete cooked a curry I helmed, and Rob and Errol tidied ship.

“Pete and Errol took the first watch at 2000 while Rob and I went below. When we came on deck just before midnight we were greeted by howling winds and ice cold spray, a maelstrom of rain moving horizontally and huge breaking seas.

“We were running under bare poles, doing up to ten knots and surfing down waves that were considerably deeper than Vyndi’s 40ft. We were pooped twice.

“By the time we handed back to Pete at 0400 we were in 60ft breaking seas with the wind gusting to 70 knots.

“I dozed fitfully and awoke when Pete came down below to fill in the log at 0600. I asked how things were going topsides and he said that it was still crazy and that he had put in a course change. I replied that at least it would be light in a few minutes and we could see what we were fighting. He went back out through the hatch.

“At 0624 there was a huge impact on the starboard side of the vessel. I felt my world spin upside-down. The shriek of the gale was silent, it was completely black and the floor was now the roof.

“We had been running ahead of a southerly gale and the course change at 0600 would have brought the marching seas even further astern; yet something, powerful enough to cross 60ft breaking seas, had picked us up and thrown us over like a toy.

“It seemed much longer than the few seconds it must have actually been until the righting momentum started. When it happened it was sudden and severe. I pulled open the hatch to witness devastation.

“The wheel had been ripped off, as had many of the deck fittings. One of the masts was hanging over the side and Errol had disappeared.

“Looking astern into a wall of water turned silver in the early morning sun, I saw Pete in the water with the ferry buoy. He called to me as he was pulled up and over the crest of the wave away from the boat. I shouted back that we would turn the yacht around as soon as we could rig some emergency steering.

“A moment later I saw him again on the crest of another 60-footer moving fast and then he was gone. We immediately fired the two parachute flares kept next to the hatch, more as encouragement for the men in the water than anything else.”

Whitbread 93/94 Dawn in the Southern Ocean aboard ‘Intrum Justitia’. Surfing in huge waves in 45 knots of wind and holding a storm spinnaker. Photo Rick Tomlinson.

An impossible scenario

“We were without steering; one mast was in the water, connected to us by a spider web of ruined rigging, the other mast had lost the shrouds on the port side causing it to sway dangerously as the vessel wallowed.”

“While Rob went below to get the spanner for the emergency tiller and send a Mayday call, I set to work jury-rigging the shrouds on the mainmast to try and secure it. The realisation that the aerial was on top of the mizzen mast, which was in the ocean, brought more consternation.

“The next problem was trying to find the custom-fit spanner for the emergency tiller. Like many indispensable items it was kept, as on all the yachts I have ever sailed on, in the ‘flip-top’ chart table, where we could all lay a hand on it at a moment’s notice. During Vyndi’s roll over, all the contents, had fallen out and were now in the bilges under two feet of water.

“Rob finally found the tool and while he started to fit the tiller I cut the mizzen wreckage away from the hull. I struggled onto the foredeck and hanked on the storm jib; at last we had power.

“The yacht answered the helm and slewed round into the wind as we headed back towards the last sighting of Pete.

“With every crest we fell off the jury-rigged mainmast swayed alarmingly. I suggested we cut it down, Rob thought we should leave it. He went below to see if he could get the engine started and it spluttered into life.

“Within a couple of minutes any debate over the mainmast became a moot point. As we fell into a trough, the tackle holding the port shroud snapped with a gunshot sound and the mast went over the side.

“I again headed onto the foredeck, this time with bolt cutters to sever the stays. It quickly became apparent that thus lightened, Vyndi was unable to make headway at the top of the crests as the wind stopped her dead.

“We were fooling ourselves. Although it appeared that we were making good progress to windward, we were going backwards. Pete and Errol, at the mercy not of the wind but of the Agulhas Current running at up to five knots, were getting further away from us all the time.

“In what was the most heartbreaking decision of my life, I told Rob that the only way our comrades in the water were going to get saved was by us turning around and trying to make contact with someone who could mobilise a helicopter. We turned around and ran with the weather.

“We decided to abandon our nearest port of safety and to sail close to the shore in an attempt to get someone to respond to a flare or distress signal. The coast from Jeffrey’s Bay to Port Elizabeth is a busy one and when we could make out individual cars travelling on the coast road we turned to run parallel with the shore.

“Over the next few hours we let off 48 flares. Not one person responded.

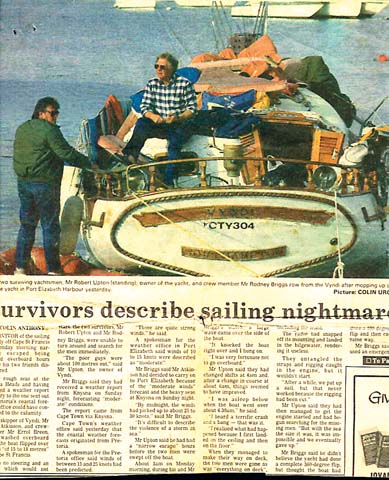

“We were met at the harbour entrance by a tug, the Captain debriefed us and radioed the details to Port Elizabeth Harbour Control.

“Nine and a quarter hours had passed since the capsize. Over the next few days the National Maritime Rescue Centre, the National Sea Rescue Institute, the police and private aircraft searched 7,500 square miles of ocean and 200 miles of coastline.

“No trace of Pete or Errol was ever found.

A hole in the ocean

“Using readings from oil rigs in the vicinity, the Oceanographic Research Institute (ORI) was able to tell me that we were sailing in 60ft breaking seas with only 27ft between each one caused by 60 knot-plus winds with a 5 knot counter-current.

“This would explain being pooped so often as Vyndi was longer than the wave intervals, but would not explain the capsize as we were running in front of the sets at the time of the impact.

“The ORI’s model for a wave large enough to cross the prevailing sets and still retain its integrity calls for the wave to be at least 30 per cent larger than the sea state it is crossing. This would require a wave 100ft high.

“As this wave approached, the water underneath the vessel would be pulled from under it leaving a ‘hole’ which the vessel would fall into. The wave would then break on top of the vessel while rolling over it.

“That is exactly what it felt like.”