The Mini 6.50 class not only attracts some of the world's best designers but many of the world's top class sailors too

As one of the smallest Open class yachts in the world, the Transat 6.50 is a class that attracts pure enthusiasts who mostly race their boats on an amateur basis. Some have been fortunate enough to gain individual sponsorship, but most struggle to do the entire campaign on a shoe-string.

Like all restricted classes, the Transat 6.50, particularly the Prototype class, is continually developing; it’s the designers’ playground. This is a class, like a development dinghy classes where high and low-tech bond together; carbonfibre/plywood, canting keels and daggerboards/fixed keels and waterballast. All the boats are different and every owner has his own ideas.

Even in the Production class (or Series Classe as it’s known in France) where the boats resemble one-designs, fitting into more stringent rules, there is an ongoing development process. This year has seen the introduction of the Pogo2 (a development of the 12-year-old Pogo), with eight boats having competed in the Mini Transat fleet.

Even in the Production class (or Series Classe as it’s known in France) where the boats resemble one-designs, fitting into more stringent rules, there is an ongoing development process. This year has seen the introduction of the Pogo2 (a development of the 12-year-old Pogo), with eight boats having competed in the Mini Transat fleet.

Compared to the Pogo, the Pogo 2 has a wider, flatter hull at the transom, a narrower bow entry and more volumn above the waterline making it extremely fast and stable downwind. Upwind performance has also been improved with the wider positioning of the rudders to help reduce drag. The rig is one of the biggest areas of change with a bowsprit and self-launch control system led back to the cockpit, replacing a standard pole.

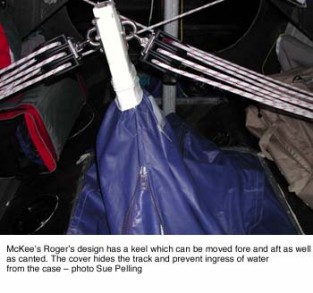

A slightly older but extremely fast example of a production boat – finishing second in the first leg of the race from La Rochelle to Lanzarote and was leading the second leg until he dismasted – is Jonathan McKee’s British Rogers design. This was one of the few all carbon pre-preg Nomex fully high-tech boats in the fleet and one of the three boats in the fleet using a system which Rogers came up with to allow the keel to move fore and aft (a maximum of 1.3m) on a track system in a keel box. So as well as canting the keel, the boat can be trimmed fore and aft as well. McKee claimed: “It’s my secret weapon. In certain conditions it can be a real bonus. I move the keel well aft downwind particularly when I’m going fast and it really does make a difference.”

A slightly older but extremely fast example of a production boat – finishing second in the first leg of the race from La Rochelle to Lanzarote and was leading the second leg until he dismasted – is Jonathan McKee’s British Rogers design. This was one of the few all carbon pre-preg Nomex fully high-tech boats in the fleet and one of the three boats in the fleet using a system which Rogers came up with to allow the keel to move fore and aft (a maximum of 1.3m) on a track system in a keel box. So as well as canting the keel, the boat can be trimmed fore and aft as well. McKee claimed: “It’s my secret weapon. In certain conditions it can be a real bonus. I move the keel well aft downwind particularly when I’m going fast and it really does make a difference.”

According to McKee the hull shape of Rogers’s design is a good all-rounder with generally good speeds upwind and offwind. Like all prototypes, the rig set up is fairly standard although McKee has rerigged the boat since he acquired it. “I changed the sheeting position to aft to keep the middle of the boat clean and it’s one of these systems where you can pull on either one or both lines, either 4:1 or 8:1; if you need to power on upwind, you pull on the 8:1 so that’s pretty good. My main aim was to keep things clean and simple and light.”

Despite the obvious disappointment of dismasting while leading the second leg of the race, McKee is still feeling upbeat about the performance of his boat believing it really has race winning potential. At the time of the breakage McKee was sailing in reasonable conditions of 15-20kts heading down the coast of Brazil, 60 miles ahead of Sam Manuard. Commenting on the boat, McKee said: “The boat was going really well, with really good speed and I was more than happy with my position. In those medium to strong upwind conditions I was stretching my distance every day and mentally uncorking the Champagne.”

With such overall consistent results it’s not surprising to hear plans of several Rogers Mini Transat designs in the pipeline. In fact, before this year’s race had even finished, Nick Bubb, the young British sailor who failed to get an entry in to the race, had sold his boat and was already hard at work at Ovington’s yard in Newcastle building the next one – a Rogers design, taken from the original plug of McKee’s boat – great news for the future of British Mini Transat sailing.