The Vendée Globe is about to meet its first Southern Ocean low. Here's what sailors are trying to do and why it could define the winner

Welcome to the Southern Ocean. The Vendée Globe leaders are on the cusp of the Roaring Forties, where they will be swept into the depressions that roil ceaselessly across the Southern Ocean.

By hooking into the right place on these depressions they could cover 500 miles a day for days on end – or fall a very long way behind their rivals. One thing’s for sure: how and when hook into the first of these depressions could define the outcome of the race.

To take a closer look at these southern low pressure systems, how they work and what the skippers will be trying to do within them, I spoke to navigator and meteorologist Chris Tibbs.

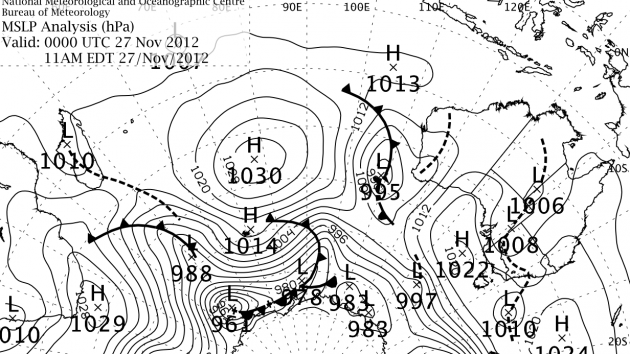

Southern hemisphere lows rotate clockwise, in the opposite direction to their counterparts north of the Equator. But that’s not the only difference. You can see from this sample synoptic chart from the Australian Bureau of Meteorology that they have a cold front but ahead of that a trough rather a clearly defined warm front.

Nevertheless, the warmer air mass ahead of the cold front has some of the same characteristics as a northern low pressure system. “There is more stable air ahead of the cold front. The gusts are less and squalls don’t really exist as such,” explains Tibbs.

The solo sailors will be aiming for this sector, shown in the screen grab above. Picking up ahead of a cold front provides safer sailing conditions, allowing them to really put their foot down. On the cold front and as it approaches you find heavy rain and squalls that can go rapidly from 40 to 60 knots, making it much harder and riskier to sail fast.

Ideally, skippers want to be sufficiently far ahead of the cold front in westerlies to ride the same weather system as long as possible. That can be a long way for the IMOCA 60s and has the potential to take them a considerable distance across the Indian Ocean, doing super-fast daily runs.

“The speed of these boats is phenomenal. If you were take an average cold front running at 25-30 knots, the catching up speed is reasonably low. If they pick up quite a few hundred miles in front and it’s only catching up at 5 knots they could ride that at a good 20 knots until the system fades, covering 500 miles a day,” says Tibbs.

It’s vital for a following pack of sailors to try and enter the Southern Ocean on the same low pressure system as the leader. If they don’t and they ‘miss the first train’, they will not be able to reach any skippers ahead – it’s not feasible to catch up across the ridges of high pressure that separate these lows.

So there’s a real possibility that winner of the Vendée Globe is in the making now. Barring damage or breakages, the victor is likely to come from the group that catches that first low pressure.

So what happens after they’ve entered a low?

The ideal situation is if there is some north in the wind ahead of the cold front. Then they will be able to hold an easterly course and scream down the course without losing mileage. If the wind is more westerly, their gybe angles would either take them closer to the centre or out towards the periphery – in either case, VMG would be less.

Eventually a system will fade or the sailors will gradually be overtaken. As the cold front approaches the wind will rotate more to the west, then afterwards the south-west. At the same time they will get heavy squalls and a worse sea state, with cross seas coming in from the south-west.

At this point they would begin to fall off the back of the cold front and fall back. Those coming up on the next low will catch and temporarily compress until they themselves fall back and the lead group is swept on to the successive low.

For a time two separate groups can seem as if it they might be about to reconsolidate, but it never happens in practice. “The leaders always seem to extend rather than contract,” says Chris Tibbs.

You can soon see all this in real life action – watch the Vendée Globe at www.vendeeglobe.org.